Summer Ground Rules

14th July

As the train pulled up to the tiny rural station, I was already waiting at the very edge of the platform, my sturdy canvas bag clutched to my chest. Inside, apples rolled around among a jar of damson jam and a Tupperware box of miniature sausage rolls. Utterly unnecessary, of coursethe children always arrived from London well-fed, their rucksacks and shopping bags burstingbut I couldnt resist making them a few things.

The doors banged open with a hiss, and out tumbled three forms: lanky, loose-limbed Daniel, his younger sister Emily, and another rucksack so big it seemed to have come alive.

“Gran!” Emily spotted me first and waved, her charm bracelet jangling.

Something warm swept into my throat. I set the bag down carefullyno sense in sending apples flyingand folded them into a hug.

“My, you two” I wanted to say “have grown,” but stopped myself in time. They knew well enough.

Dan ambled over, offering a one-armed hug, the other holding firm to his rucksack.

“Hi, Gran.”

He stood nearly a head taller now, a shadow across his jaw, narrow wrists, headphones peeking out from a torn t-shirt. I found myself searching for the boy who once dashed about our garden in green wellies, but all I could see was the grown person hed become.

“Grandads waiting in the car,” I said, almost reluctant to break the moment. “Lets get a move onmy beef patties are getting cold.”

“Just one photo,” Emily had already whipped out her phone, photographing the station, the train, me. “For my story.”

The word “story” flashed by, unrecognisable. Id asked my daughter last winter what that meant, but the explanation vanished from my mind. No matter. Emily was smiling, and that was what counted.

We made our way down the concrete steps. Old Henry waited by the battered Land Rover. He straightened, clapping Dan on the shoulder, embracing Emily, and giving me one of his calm nods. Always more subdued, but I knew he was as happy as I was.

“Soschool holidays at last?” he asked.

“Finally,” said Dan, hurling his bag into the boot.

The children fell quiet on the drive. Outside, gardens and allotments rolled past, with the odd goat amidst the hedgerows. Emily fiddled with her phone, Dan chuckled at something on his screen, and I watched their fingers, constantly stroking those little black rectangles.

Never mind, I told myself. So long as home felt like home. The rest could be how it is nowadays.

We arrived to the aroma of sizzling patties and fresh dill. On the veranda, our old table stood dressed in a lemon-patterned oilcloth. The pan hissed on the stove, a savoury pie baked in the Aga.

“Wowfeast!” Dan peered into the kitchen.

“Just lunch, not a feast,” my old instincts replied before I caught myself. “Come on, go wash your handsover by the sink.”

Emily was already at it again with her phone. Out of the corner of my eye I saw her snapping pics of the plates, the sunshine through the windows, and Poppy the cat slinking cautiously from under a chair.

“No phones at the table,” I said gently when we settled.

Dan glanced up, puzzled.

“What do you mean?”

“She means, after food you can have all the phone you want,” Henry chimed in.

Emily hesitated, then placed her phone face down.

“I just want a photo”

“Youve got plenty, love,” I said softly, placing the salad and bread out. “Eat first, stories later.”

The word “post” felt clumsy in my mouth, but I hoped it landed close enough.

Dan, after a pause, slid his phone to the corner of the table, like hed been asked to leave his spacesuit at the door of a spaceship.

“Theres a schedule,” I explained as I poured squash. “Lunch at one, tea at seven. In the mornings, no lie-ins past nine. After that, youre free to do as you like.”

“Not past nine?” Dan protested. “But what if Im up late watching a film?”

“People sleep at night,” Henry said calmly, not looking up from his potatoes.

I felt a tremor of tension between us, so I rushed in,

“Its not meant to be like a barracks. But if you sleep till midday, the days wasted. Theres the river to explore, woods, bikes out back”

“I want the river, and a bike, and a photoshoot in the garden,” Emily declared quickly.

“Splendid,” I nodded. “But first, a bit of help. Potatoes to weed, strawberries need watering. Youre not here for a holiday camp!”

“But, Gran, its meant to be holidays” Dan started, but Henry gave a stern look.

“Holiday, not a hotel,” he replied.

Dan sighed but said nothing. Emily nudged his trainer under the table and he almost smiled.

After lunch, they vanished to unpack. I popped my head in after half an hour. Emily was already hanging t-shirts on the chair, make-up perched on the windowsill. Dan sat on the bed, lost in his phone.

“Ive changed your sheets,” I said. “Anything wrong, let me know.”

“All good, Gran,” he muttered, eyes fixed on the screen.

That “all good” somehow stung, but I just nodded.

“Barbecue laterafter youve had a cup of tea, pop out and give us a hand, will you?”

“Okay,” said Dan.

I left, listening to Emilys giggle over a video call. And suddenly, I felt oldnot aching, but as if their lives moved on a different level entirely, just out of reach.

Its alright, I told myself. Well muddle through. The point is not to smother.

That evening, the golden light skimming the fields, we were out in the garden. The earth was warm, crispy grass underfoot. Henry showed Emily the difference between weeds and carrot tops.

“That one, pull. This one, leave,” he instructed.

“And if I mess up?” Emily wrinkled her nose, kneeling.

“It wont matter,” I said. “Were not running a commercial farm.”

Dan loitered, leaning on the hoe, eyeing the glow from the monitor in his window.

“Not afraid youll lose your phone?” Henry asked.

“Left it upstairs,” Dan muttered.

For some reason, this pleased me more than it should.

The first days found us in a tentative rhythm. Id rap on their door every morning, they’d grumble but, by half nine, appeared in the kitchen regardless. Breakfast, a touch of tidy-up, then they scattered: Emily staged photoshoots with Poppy and the strawberries to post online, Dan alternated between reading, music, or cycling until tea.

Our rules ran on details: Phones off the table. Silence after midnight. Only one time, the third night, I caught myself awake at a faint giggle through the wall. The bedside clock read half one.

Should I intervene or leave it?, I wondered.

Another giggle, a muted voice message ping. I sighed, put on my dressing gown, and knocked gently.

“Dan, you awake?”

The laughter stopped.

“Yeahhang on,” a low voice replied.

He opened the door, blinking into the hallway light, eyes rimmed slightly red, hair in a wild mop, phone in hand.

“Why arent you asleep, love?”

“I was watching a film.”

“At one in the morning?”

“Yeah, were syncing itmessaging together. With my mates.”

I pictured other kids in city flats, in the dark, chatting away while watching the same film.

“Listen,” I said. “I dont mind the film, honestly. But if youre up all night, youre rubbish in the morning, and I need you outside later. Lets agree: midnights the cut-off, alright? After that, switch off.”

He pulled a face.

“But they”

“Theyre at home, youre here. Our ways, love. Im not asking you to be in bed at nine.”

He scratched his head, then nodded.

“Midnight,” he said.

“And close the door, light gets in. Lower the volume too, please.”

Returning to bed, I wondered if Id gone soft. Maybe I should have been stricter, like years ago with my daughter. But times change.

Grumbles began to grow from the little things. One sweltering morning, I asked Dan to help Henry shift the timber by the shed.

“Im coming,” he muttered, glued to his screen.

Ten minutes passedhe hadnt moved.

“Dan, your grandads moving them alone now,” I said, voice sharper than I meant.

“Ill just finish typingthen Im there,” came the irritable reply.

“Whats so vital youre always messaging? The world wont stop!”

He looked up, annoyed.

“Its important,” he retorted. “Were mid-tournament.”

“What tournament?”

“In the game. Its a team match. I leave, we lose.”

I wanted to say there were more important things, but I saw his jaw clench, his shoulders tense.

“How long will you be?”

“Twenty minutes.”

“Right then. Twenty minutes, then you help. Agreed?”

He nodded, eyes back to the phone. Exactly twenty minutes later, he appeared, tying his trainers.

“Im going, alright?” he said, before I could open my mouth.

Tiny agreements kept things ticking. But of course, it couldnt last.

It happened in July, just as we planned to go to the Saturday market. Henry stressed hed need help: bags would be heavy, and the car shouldnt be left unattended.

“Dan, youre coming with grandad tomorrow,” I said at tea. “Emily and I will stay, make jam.”

“I cant come,” Dan replied at once.

“Why not?”

“Im off to town with my matestheres a festival, a gig, food stalls I did tell you.”

Perhaps he had, but I didnt recall. Wed had so many conversations lately.

“Which town?” Henrys brow furrowed.

“Our local one. By train. The festivals not far from the station.”

The phrase “not far” had never comforted him.

“You know the route?”

“Therell be loads of us. And Im sixteen.”

That “sixteen” was supposed to settle everything.

“We promised your dad not to let you go wandering by yourself,” Henry said.

“I wont be alone. My friends are coming too.”

“Thats exactly why!”

Tension thick as porridge. Emily scraped up the last forkful of pasta, sliding her plate away.

“Why not go to the market tonight and let him go with his mates tomorrow?” I suggested.

“Markets only open tomorrow,” Henry said, stiff. “I need help.”

“Ill go,” Emily piped up.

“Youre staying with your granny,” he replied automatically.

“I can manage on my own,” I said. “Jam can wait. Emily can help you.”

For a second, Henry looked at me with disbelief, thanks, and a stubborn something else.

“And what about this one?” he gestured at Dan.

“I just” Dan began.

“You realise youre not in London? Its different here. Were responsible for you.”

“Someones always responsible for me,” Dan shot back. “Can I ever just decide for myself?”

Silence crashed down. My heart twisted. I wanted to say I understood, that Id once yearned for independence, too. Instead, the words came out flat:

“While you live with us, you follow our rules.”

He jerked his chair back.

“Fine. Im not going anywhere.”

He left, the kitchen door banging. Moments later a muffled thump came from upstairseither his bag hitting the floor or himself, sitting heavily back on the bed.

The evening limped by. Emily tried to make us laugh, talking about some influencer online, but no one could muster a real smile. Henry stared into his tea. Washing up, my words echoed in my head like a spoon in a jar: “our rules.”

The night was unusually quiet. I woke, expecting the usual creaks and the odd fox, but there was nothingnot a glimmer under Dans door.

Maybe, I thought, at least hell have a good sleep.

In the morning, Emily was already yawning at the kitchen table, Henry reading his newspaper.

“Wheres Dan?” I asked.

“Asleep?” Emily suggested.

I went up, knocked. No answer. The bed was poorly made, just as he always did it when forced. No Dan. His hoodie slung on the chair, the charger on the desk. His phonegone.

Something in my stomach dropped.

“Hes not there,” I called back downstairs.

“What do you mean not there?” Henry came rushing.

“The beds empty. Hes taken his phone.”

“Out in the yard?” Emily guessed.

We scoured the place. The shedno sign, nor in the garden. The bikestill in the rack.

“First train was at eight forty,” Henry said, glancing towards the lane.

My palms went cold.

“Maybe just to see some local lads”

“What lads? He doesnt know anyone here.”

Emily picked up her phone.

“Ill text him.”

Her fingers flew. After a while, she looked up.

“Hes not seen it. Still one tick.”

The phrase meant nothing to me, but Emilys anxious face told me it mattered.

“What now?” I asked Henry.

He paused.

“Ill go check the station. Someone mightve seen him.”

“Are you sure?” I asked hesitantly. “Maybe hes just”

“He went without a word,” Henry cut in. “Its not nothing.”

He dressed hastily, grabbed the car keys.

“You stay put,” he said to me. “If he comes back, text me. Emily, if he gets in touch, let me know right away.”

Once the car rumbled off, I sat on the step with a cleaning cloth twisted in my hands, my mind racing with awful scenes: Dan at the platform, boarding the train, pushed, lost, hurt I tried to stop myself.

Calm, hes not a little boy. Hes not silly.

An hour crawled by. Then another. Emily kept checking her phone.

“Still nothing. Hes not online,” she whispered.

By eleven, Henry washome, face exhausted.

“No one saw him. I even checked by the station,” he started, trailing off. I knew what that meant.

“Maybe he went anyway. To that festival,” I said.

“No money, nothing?” he frowned.

“Hes got a card on his phone,” Emily interrupted. “That works everywhere.”

We exchanged looks. Money, for our generation, belonged in purses; for them, it fluttered in the ether.

“Should we call his dad?” I suggested.

“Yes,” Henry agreed gruffly. “Hell need to know.”

The phone call hurt. My sons voice: angry, worried, accusing. Why hadnt we watched him? I finished the call wrung out, sinking onto the stool and covering my face.

“Gran,” Emily pleaded, “hes not missing. Hes just cross.”

“Cross enough to disappear,” I replied. “Like were the enemy.”

The day dragged on. We forced ourselves to make jam, Henry tinkered in the shed, but everything felt unnatural. Emilys phone stayed silent.

By evening, the door let out a creak. I started. The gate scraped. There he was in the dusk: Dan, the same grubby jeans, his rucksack, looking tired but whole.

“Hi,” he murmured.

I stood and wanted to embrace him but stopped myself.

“Where were you?” I asked.

“In town,” he looked down. “The festival.”

“Alone?”

“With my friendsfrom the next village. Arranged it online.”

Henry appeared, wiping his hands.

“Do you have any idea” His voice broke.

“I textedI lost signal. Then the battery died. I forgot the charger.”

Emily joined us, phone now a lifeline.

“I tried you. You only had one tick.”

“I wasnt ignoring you,” he said, glancing at each of us. “I just I knew if I asked, you wouldnt let me. And Id already said Id go. So”

“You decided best not to tell anyone,” Henry finished flatly.

A heavy silence tightened between us. But it was shaded now with weariness, not only frustration.

“Come in, love,” I said eventually. “Eat first.”

He followed me quietly to the kitchen. I ladled out soup, set out bread, poured squash. He ate as if he hadnt eaten all day.

“Everythings expensive at those food stalls,” he muttered.

The “those” was odd, but I let it slide.

Later, in the dusk, we sat outside on the step. The air was cooler now.

“Lets do this,” Henry said, settling beside him. “You want freedom, fine. But while youre here, we have to know where you are. If you want to go somewhere, say it upfrontnot the night before, but in advance. Sort your train times, your mates, who meets you. We discuss it properly. If we agree, you go. If not, you stay. But no more vanishing acts.”

“And if you say no?”

“You get cross but stay,” I joined in. “We get cross too, but drag you round the market.”

He looked at me, his eyes a tangle of tiredness, annoyance and something fragile.

“I wasnt trying to scare you,” he said. “Just wanted to make my own decisions.”

“Its good to decide for yourself,” I said. “But its also about caring for the people who worry when you dont come back.”

I was surprised at myself; it was not a telling-off, just a fact.

He sighed.

“Alright. Understood.”

“One more thing,” Henry added. “If your phones dying, find somewhere, charge it. Café, stationanywhere. Message or call us, even if you think well tell you off.”

“Alright,” Dan nodded.

We sat without speaking. A dog barked somewhere over the hedge. Poppy meowed lazily in the veg patch.

“How was the festival?” Emily piped up.

“Alright. Music was rubbish, but the food wasnt bad.”

“Got any photos?”

“Phone died.”

“Great,” she groaned. “No proof, no content!”

Dan almost grinned. The tension finally eased.

Life changed, just slightly, after that. The rules didnt disappear, but they bent and swayed. That evening, Henry and I wrote it out on a sheet: up by ten, two hours help a day, let us know if youre going anywhere, no phones at meals. We stuck it to the fridge.

“Feels like summer camp,” Dan grunted.

“Family camp, not a boot camp,” I winked.

Emily had rules to add too.

“You dont phone me every five minutes if Im down the road, and knock before you come in,” she said.

“We never barge in,” I said, honestly shocked.

“Write it anyway,” Dan insisted. “Fairs fair.”

We wrote two more lines. Even Henry grumbled, but signed his name.

Gradually, shared tasks turned from chores to their own sort of fun. One afternoon, Emily dug out a board game from the sheda childhood relic.

“Lets play tonight!”

“I used to be a pro at this!” Dan brightened up.

Henry tried to protestclaimed work to dobut joined in. He remembered the rules best of all. We bickered, laughed, playfully sabotaged each others moves. Phones, for once, lay forgotten.

Saturday, I declared, would be their turn to cook dinner.

“Really? Us?” both Dan and Emily cried in horror.

“You. Anything, as long as its edible.”

They took it seriously: Emily found a recipe online for something trendy, Dan chopped veg, both debating every sauce and slice. The kitchen filled up with the smell of onions, an ever-growing tower of dirty dishes, and a sense of event.

“Dont blame me if we all end up queueing for the loo,” Henry gruffly jokedbut he ate every bite.

We compromised in the garden too. No more daily weed-wars; instead, I gave them their “own plots.”

“This rows yours,” I told Emily, pointing to the strawberries. “And this,” nodding toward carrots, “Dans.”

“Do what you likeif it withers, dont blame me.”

“Experiment,” Dan said.

“Control and test group!” Emily added.

She watered her plot daily, photographed every berry, made posts about “my summer garden.” Dan watered his carrots once, then forgot. At digging-up time, Emily had a basketful, Dan had three scrawny carrots.

“Lessons learned?” I asked.

“Carrot-farming is a racket,” Dan replied perfectly straight-faced.

We all laughed, real laughter this time.

As August waned, the house clicked into its own gentle tempo: breakfast, days adventures, shared dinner. Dan, sometimes, stayed up past midnight with headphones, but always switched the light off at twelve, and when I passed, he was sound asleep. Emily might head to the river with the neighbours daughter, always texting where shed gone and when shed be back.

Of course, we still arguedabout music, soup salt levels, whether to wash up tonight or leave till morning. But it stopped feeling like a battle. More like the little grumbles of everyday life together.

On the very last evening, I baked an apple tart. The air filled with sweet warmth; on the table, bags and neatly folded piles of clothes were ready to go.

“Lets do a photo,” Emily said as she sliced the tart.

“Not more of your” Henry began, but checked himself.

“Just for us,” she smiled. “Not for Instagram, promise.”

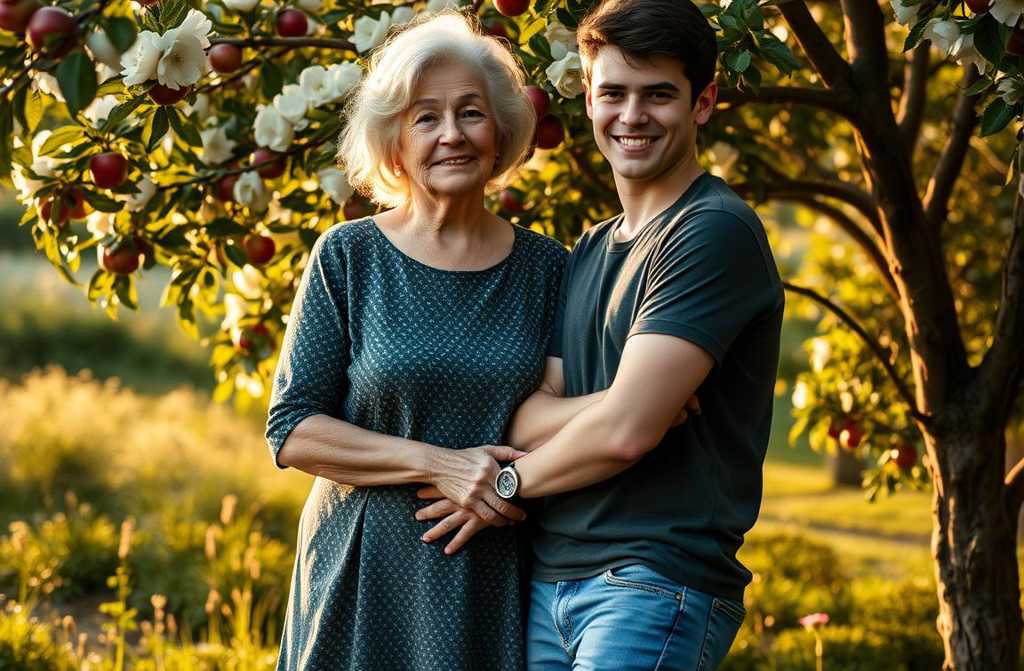

We trooped into the garden. Sunset turned the apple trees gold. Emily propped her phone up on an upturned bucket, set the timer, and rushed back.

“Gran in the middle, Grandad on the right, Dan on the left.”

We lined up, not a little awkwardly, shoulder to shoulder. Dan touched my elbow, just for a second. Henry moved in close too. Emily threw her arms around us all.

“Smile!” she called.

The shutter clicked once, twice.

“Lets see,” I asked, as she checked the screen.

We looked slightly ridiculousme with my apron, Henry in his threadbare shirt, Dans hair wild, Emily in her bright top. But there we were, together, something strong and unmistakable in our jumble.

“Can you print me that?” I asked.

“Of course.” Emily beamed. “Ill send it to you.”

“How will I print it? Its on your phone!”

“Ill help,” Dan chipped in. “Come visit in the autumn, well sort it. Or Ill post you a copy.”

I nodded. I felt settlednot because we suddenly understood each other perfectly, but because there was, at last, a little footpath between our house rules and their freedoms, one we could all walk, to and fro.

Late that night, after the house had gone quiet, I stepped onto the veranda. The stars pricked faintly over the rooftops. I tucked my knees to my chest, breathing the cooling air.

Henry joined me, slumping onto the step.

“Theyll be off tomorrow,” he said.

“They will,” I agreed.

We sat in the peaceful dark.

“You know,” he said quietly, “its worked out alright.”

“It did,” I said. “And maybe we all learned something.”

“Not sure who learned more,” he smirked.

I smiled. No light glowed in Dans window, nor Emilys. Somewhere, Dans phone recharged quietly, ready for the journey tomorrow.

I rose, bolted the door, and glanced at the fridgeour summer ground rules sheet still hanging there, curling a little at the corners. I ran my finger over the list of names and thought, perhaps next year, well rewrite it. Something will change, maybe. The important bits will last.

I flicked off the light and climbed into bed, breathing slow and full, knowing our home was calm tonight, filled with all the summers laughter, and roomalways roomfor something new.