For ten years I laboured as a cook in my sons house and received not a shred of gratitude.

She had been a schoolteacher, retiring at fifty-five. That was when she settled into her sons home in Oxfordshire, sealing up her own little flat near the railway. Oddly, she never rented it outperhaps a quiet worry kept her away, something whispering at the edge of dreams.

With her son and daughter-in-law, things were simple but steady, no quarrels or rifts; their days flickered by in something like harmony. But Ive always believed this woman achieved something extraordinary. She moved in just as her grandson turned one, and for a decade she lived as part of their household.

Her daughter-in-law soon returned to her office job, and suddenly, the whole burden of the housewhat I can only call a domestic stormfell upon the grandmother. Above all, the care of a small child, which weighs on the soul as much as the arms. Its not something everyone finds within themselves.

From sunrise to sunset she was nurse, chef, cleaner. The young couple drifted through the door at seven, and only then could she rest her bones, before the next sunrise swept her up again.

Years passed, and when the boy started school, the strangeness only changed its shape. That meant the No. 2 bus! Each morning, the grandmother would bundle him up and take him in, then wait at the school gates in the afternoonsdoing this till he was almost in secondary, all the while folding laundry and stirring pots.

She told me sometimes, when evening arrived, she couldnt even keep her eyes open for the tellyshed fall asleep before the theme tune. No tea with friends, no afternoons out, nothing. On bank holidays, the young ones would vanish off to some gathering, leaving her to sit with the boy.

And then, with the grandson almost ten, perhaps she would have carried on forever, if not for a peculiar spark of fate. One day, hidden just around the kitchen door, she overheard her daughter-in-law murmuring: Your mums always putting too much powder in the wash, thats why our sheets smell odd. You ought to mention it quietly. Ten years scrubbing laundry, and only now this?

She swallowed the bitterness, tried not to let it sprout.

The second sign came swiftly. The daughter-in-law suggested, sweetly, that perhaps the boy might need his own room, and could she, the grandmother, move into the corridor room? Something flickered in herrealisation.

She packed her things, dusted off her own old flat, ran the taps, wiped down the windows, and settled herself back home. Yet, something important shifted: her son and daughter-in-law were wounded at her departure. Perhaps theyd imagined shed work there till the end of days, become part of the wallpaper, invisible and tireless.

Whats sorrowful is how no one pitied her, as though all shed done was just the natural orderscrub, cook, wash, polish. As though she felt no weariness, as though she was more shadow than person.

They sulked and stressed, even stopped speaking to her for a spell. But shes an optimist; she believes things will heal in time.

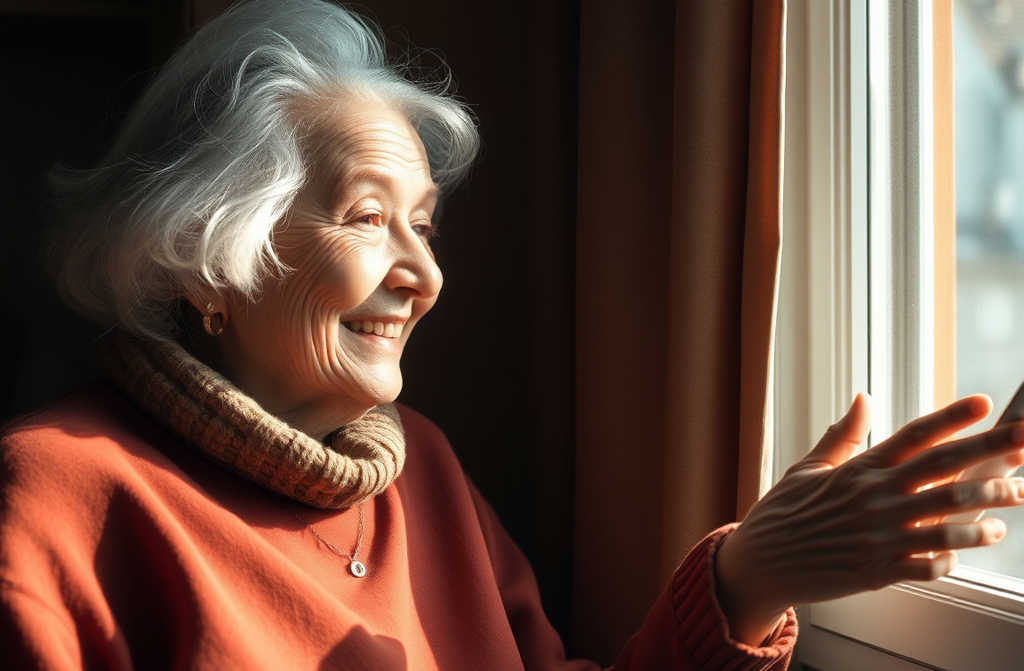

Now she celebrates real joy: she can live for herself. She doesnt rush anywhere, the burden is gone. And what does one really need for happiness?

So, at sixty-five, shes found delight once more. Do you recall the lyric? Second youth comes to those who preserve the first. At last, she felt that magic of releasethe right to exist for herself, to be free from endless duty.

Perhaps selflessness is a fanciful word. Perhaps. But its real.

I wonder if anyone truly recognises such sacrificeperhaps not even our own children. We grow so fast used to the comfort of someone else scrubbing, boiling, laying tables, clearing dishes, folding towels, shepherding the childrenfeeding them, settling them to sleep, doing the homework. How quickly we become accustomed to safety, warmth, and care. How quickly we forget!