Nobodys Home

George woke up without any alarm, just as he always did, at half past six. The flat was quiet, the only noise being the gentle hum of the fridge in the kitchen. He lay there for a moment, listening to it, then reached for his glasses on the windowsill. The sky outside was dreary and grey, with the odd car whisking past on the damp tarmac.

He used to get ready for work at this time. Up, into the bathroom, hearing his neighbour flick on Radio 4 through the wall. Now, the neighbour still listened to the radio, but George would just lie there thinking about what hed do today. Technically, hed been retired three years now, but old habits die hard. He kept his routines.

Slipping into a pair of tracksuit bottoms, he wandered into the kitchen, flicked the kettle on and pulled out a bit of yesterdays white bread from the bread bin. While the kettle boiled, he went to the window seventh floor, concrete block, the courtyard below with the childrens playground. His battered old Astra sat underneath, dust gathering on the roof. He mentally made note to pop round to the garage, see if the roof had started leaking again.

The garage was in a little row of lockups a few bus stops away. Back in the day, thats where hed spend half the weekend: tinkering with the car or changing the oil, having a natter with the lads about the price of petrol or the state of the football. That all changed. Now, everything was easier: garages, tyre shops, click & collect. But hed never given the garage up. Thats where his spanners were, and the old tyres, and those boxes of bits and bobs, as he called them.

And then there was the allotment. Well, it was really a modest wooden hut in a little village outside town, in an allotment community. Two rooms, that poky kitchen, a rickety porch. If he closed his eyes, George could picture every floorboard, every crack, remember the sound of rain tapping on the roof. Theyd inherited the plot from his wifes parents, donkeys years ago. For more than twenty years, most weekends were spent there with the kids: digging up potatoes, frying up sausages, dragging the old radio out onto a stool.

His wife had been gone four years now. The kids were grown up, scattered about town with families of their own. The plot and the garage still clung to him, like pins on a map that showed he belonged somewhere. Here was home. Here was the plot. Here was the garage. Everything in its place.

The kettle whistled. George made his tea, sat at the table. The cardigan hed folded up the night before sat on the chair opposite. He munched his toast, staring at it, and thought back to the conversation yesterday.

The kids had popped round last night. His son with his wife and young boy Georges grandson. His daughter with her husband. Theyd all shared tea, chatted about holidays. Then, inevitably, the subject of money came up, just as it always did nowadays.

His son went on about the mortgage always going up, interest rates through the roof. His daughter complained that nursery fees kept climbing, then there were after-school clubs, clothes, the lot. George nodded, remembering the days hed scraped together pennies before payday himself. But back then, he hadnt even dreamed of a plot or a garage. Just a rented room and some hope.

Then, after a bit of shuffling, his son said:

Dad, so weve been talking, me and Emma, and talked to Sophie too. Maybe you should think about selling something? The plot, maybe. Or the garage. You hardly go anymore, do you?

George had made a joke of it, changed the subject. But that night, hed lain awake hearing the phrase you hardly go whisk around in his head.

He finished his toast, drained his tea and put the mug in the sink. It was eight oclock. He decided hed go to the plot today. Best check how it had coped with the winter. And maybe maybe prove something to himself.

He wrapped up warm and grabbed the keys for the plot and the garage from the hook in the hallway, slipped them into his jacket pocket. He caught himself in the old mirror, the frame still painted by his wife all those years ago. Reflected back: a silver-haired man, eyes a bit tired, but still strong. He straightened his collar, headed out.

He swung by the garage first to grab some odds and ends. The lock gave its familiar groan, and the door stuck, as always, before popping open. That old smell hit him a mix of petrol and dust and musty rags. Shelves lined with jars of screws and bolts, boxes crammed with wires, an old cassette marked up with Top Pops 86. Cobwebs drifting in the rafters.

He ran his eyes over the shelves. There the old jack from his first car. And a pile of timber hed meant to turn into a bench for the plot. He never did get round to it. But the wood still waited.

Tools and a couple of plastic jerry cans in hand, he locked up and set off.

The drive out took about an hour. Muddy snow still lingered against the kerb, bits of black earth poking through. The allotment was quiet. Too early in spring yet for a crowd. The warden, Mrs Barnes, gave him a nod in her puffy coat as he pulled up.

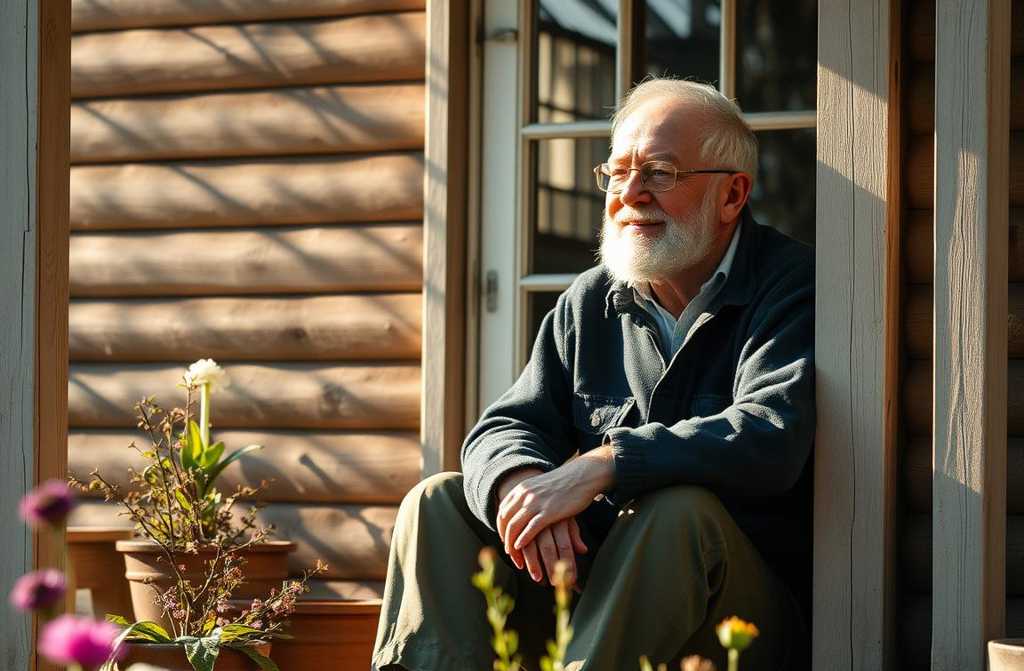

The shed welcomed him with the same silence it always had at this time of year. Wooden fence, wonky gate. He pushed it open, picked his way along the narrow path to the porch. Leaves from last year crackled underfoot.

Inside was damp and woody. George flung open the windows wide. Pulled the faded sheet from the bed, shook it off. In the tiny kitchen, the old blue pan was still on the table, from when they used to make jam. A ring of keys still hung by the door, one for the shed stuffed with spades and forks.

He wandered room to room, brushing his fingers across handles and walls. In the room where the kids had slept, the bunk bed was untouched. The top bunk was home to a stuffed bear with one ear missing. George remembered the tears when that ear had come off, and how hed patched it up with electrical tape instead of glue.

He stepped out to the plot. Last of the snow had melted, soil dark and wet. The rusty barbecue sat at the back, listing to one side. He remembered grilling burgers, he and his wife sat on the porch with mugs of tea, while laughter echoed from neighbouring plots.

With a sigh, George shook off the memories and got stuck in: clearing the path, re-nailing a loose plank on the porch, checking the shed roof. He found an old plastic chair, carried it out to the garden, sat down. The sun had climbed, and it was almost warm.

He took out his phone, scrolled through the missed calls. His son had rung last night. His daughter had messaged to say, We should all get together and talk calmly. We dont mind the plot, Dad we just need to be sensible, shed written.

Sensible. Hed heard that word a lot lately. Sensible meant money shouldnt be wasted. Sensible meant an older man shouldnt wear himself out on sheds and gardens. Sensible meant help the children now, while youre still here.

He got it. He really did. But every time he sat on that chair, dog barking in the distance, rain dripping from the gutter, sensible faded into the background. This was all about something else.

He got up, took one last stroll around, locked up tight. Drove back to town.

He was home before lunch. He hung up his jacket, left the bag of tools in the hall. Switched the kettle on, and only then noticed a note on the kitchen table. Dad, well pop over this evening to talk. G.

He sat down, hands pressed to the table. Right, then. Tonight would be the real heart-to-heart, no more skirting around.

They came over in the evening the son and his wife, and his daughter. Grandson left with Emmas mum. George opened the door, greetings, the familiar awkward tripping over shoes in the narrow hallway like old times.

They sat at the kitchen table. George put out the biscuit tin, sweets, made tea. No one touched a thing for a while. Small talk filled the silence hows work, hows the little one, traffic terrible isnt it.

After a long look across the table, his daughter spoke up.

Dad, lets talk properly. We dont want to hassle you, but we do need to figure things out.

George felt something knot inside. He nodded: Go on.

His son began, Youve got the flat, the plot and the garage, right. The flat we wont ever touch that. But the plot youve said its hard work: gardens, the roof, fences, always costs each year.

I was there today, George replied quietly. Everythings alright.

Thats now, piped up his sons wife. But what about five years from now? Ten? You arent going to be around forever. Im sorry, but we all have to think about that.

He couldnt look at her too blunt, even if she didnt mean to hurt.

His daughter spoke up, a bit softer. Dad, were not saying ditch it all. But maybe you should sell the plot and garage, and split the money. Keep some, and help us out a bit. We could pay down the mortgage. Youve always said you wanted to help.

He actually had, at some point, when retirement felt like a never-ending weekend and he could do odd jobs on the side. Back then, he thought hed be fit forever.

I do help, he said. I do the odd bit of babysitting, pick you up shopping.

His son gave a nervous laugh, Dad, thats not the same. Were talking about a decent bit of money that could really ease the pressure. Theres property just sitting there gathering dust.

In this house, George thought, even the word property felt out of place. There was a silent pillar rising between them numbers and bank statements and loan contracts.

He reached for his cup, sipped cold tea.

For you, its property, he said slowly. For me

He paused, looking for the word. He didnt want to be dramatic.

Its bits of my life, he managed. I built that garage myself. With my dad. Brick by brick. And the plot, well thats where you two grew up.

His daughter looked down. After a moment, his son said, gentler than before, We do get that. But you hardly ever go now. It all just sits there. You wont be able to manage on your own for long.

I was there today, George repeated. All fine.

Today, said his son. But the last time? Autumn, maybe? Dad, be honest.

The room was still for a bit. George could hear the ticking clock in the next room, sense that the talk was no longer about the plot or the garage, but about his old age, like some kind of project: downsizing, redistribution.

Fine, he asked. What do you actually want to do?

His son perked up they’d clearly talked this over.

Weve got an estate agent lined up. She reckons she can get a decent price for the plot, and we can flog the garage too. Well sort all the viewings and the paperworkjust need you to sign one form.

And the flat? George asked.

Wed never touch the flat, his daughter said quickly. Thats your home.

He nodded. The word home suddenly sounded uncertain. Did home only mean these four walls? Or did it include the plot, the garage? Places hed poured hours into, swearing at rusty nuts or sanding shaky floorboards, but always feeling he belonged.

He got up and walked to the window. The streetlights flickered on in the estate below. All looked the same as twenty years ago: new cars, children with phones on the swings.

And if I dont want to sell? he asked quietly, still staring outside.

Silence. Then his daughter cautiously said: Its yours, Dad. Its your call. We cant force you. We care about you. Youve said yourself youre not as strong these days.

He agreed, True. But Im still capable of deciding what to do.

His son sighed, Were not here for a row, Dad. But youre clinging to things, and were struggling, both with the stress and money side. And were always worrying what happens if you get ill whos going to look after this stuff?

A twinge of guilt flared in George. Hed had that thought himself. What if he just wasnt here, one day? The kids would be left to wade through paperwork, parcel it all up. No easy task.

He sat back at the table.

What if He stopped. What if we sign the plot over to you and Sophie, split it. But dont sell. Ill keep going there while I can.

The siblings exchanged glances. His daughter-in-law frowned.

But Dad, that just leaves the problem hanging. We cant go down there as often as youd want. Were busy, kids, jobs

Im not asking you to, he replied. Ill handle it. For as long as Im able. After that well, youll do what you think best.

It was a compromise, and they all knew it. For George, a chance to hang on to his patch for a bit longer. For them, comfort in knowing the paperwork would be in order.

His daughter seemed to consider it. Maybe. But honestly, Dad were never going to live there. Were thinking of moving out of town anyway. Place is cheaper up north. There are jobs.

That startled George. He glanced at his son, who looked surprised.

You never said, said his son.

Were just thinking, she replied, brushing it off. But thats not the point. The plot isnt our future, Dad. Its not the same for us as it is for you.

He picked up on that word future. For them, the future was somewhere else: a new city, a new scheme. For him, it was shrinking to a handful of places flat, plot, garage places where he knew every corner.

And so they went round and round, for another twenty minutes: them with their numbers, him with his memories. They talked about health, he about how busy hands keep you sane. In the end, his son lost his patience, Dad, you cant keep this up forever. Therell come a time you cant go, cant dig. What then? Itll all fall apart, rot. Well visit once in a blue moon, stare at a collapsing hut.

Thats what it is to you? George asked, stung. You ran around there as a boy.

In those days, yeah, said his son. But Im a grown man now. My lifes elsewhere.

The words hung awkwardly. His daughter tried to soften, Tom, dont

But it was too late. George realised something: they werent even speaking the same language anymore. For him, that time, that place was life itself. For them, it was just the past a nice memory, but not essential.

He stood up, Right then. Give me time. Not tonight, not tomorrow. I need to think.

Dad, his daughter started, but weve got a payment coming.

He interrupted. I know. But you have to understand too. This isnt like selling a cupboard, is it?

They all went quiet and then got up to leave. The hallway was full of awkward farewells. His daughter did hug him, her cheek pressed warm to his.

We arent against the plot, Dad. Honestly. We just worry about you.

He just nodded, unable to speak.

When the door clicked shut, the silence in the flat closed in. George drifted into the kitchen and sat back at the table. The cold tea and biscuits lay untouched. He just sat, no lights on, as dusk slipped into night outside.

Eventually he stirred, walked into the lounge, pulled the folder with all the documents from the cupboard: passport, deeds to the plot, garage papers. A plan of the farming beds neat little rectangles marked out. He ran a finger across them, as though across the soil itself.

The next day he went to the garage. Needed something to do, to feel useful. He let the big metal door swing wide, chased the stale air out. He sorted boxes, cleared old junk at last: cracked pipes, rusty bolts, wires hed kept, just in case.

Old Bill, the chap in the garage next door, poked his head round, Getting rid?

Tidying up, George replied. Deciding whats still useful to me.

Good on you, Bill grinned. I sold up last month. Gave the cash to my son for a car. Garage is gone, but at least hes happy.

George didnt answer. Bill drifted off, leaving him alone with his thoughts. It all sounded so simpleselling up. Like deciding to sling out an old jacket.

He picked up a battered spanner, smooth now after all those years. Fitted it in his hand, mimed ratcheting a bolt. Remembered his son as a lad, wide-eyed, eager to try it too. Back then, hed thought theyd always share these places, this language of shed and car and plot.

Now he saw: for his son, that language had vanished.

That evening, George got the folder out again. Sat with it for a long while. Then phoned his daughter.

Ive made up my mind, he said. Lets sign the plot over to you and Tom. But equal shares, and we arent selling it now. While I can, Ill go. After that, you do what you need to.

There was a pause.

Are you sure? she asked gently.

He was quiet for a moment, but then, Yes. Im sure. But in his chest, it felt like losing something precious. Still, what else was there to do?

Alright, she said. Lets meet tomorrow, sort it.

He hung up and just sat there, relief and sadness mingling as if a weight had shifted, but not in the way hed wished.

A week later, they were at the solicitors. Signed over the plot as a gift. Georges hand trembled just a little on the forms. The solicitor explained where to sign, what to keep. The kids thanked him, grateful.

Thank you, Dad, Tom kept saying. It means a lot.

George nodded, but deep down he knew he wasnt just helping them out. In a way, theyd helped him, freeing him from worrying about what next. The future was written down, at last.

He kept the garage. For now. The kids hinted again, but this time he was firm: Thats staying with me. They saw that he needed somewhere to go, something to do, some reason not to melt away in a haze of daytime telly. They understood.

Nothing much seemed to change afterwards. He still lived in his flat, popped out to the plot some weekends, but now as a visitor in a place that, on paper, wasnt his anymore. But the keys were still in his pocket, and no one stopped him.

The first time he returned, it was a bright April day. On the drive, he wondered if itd feel strange, now it wasnt his. But when he unlocked that gate, when the path to the porch crunched underfoot, it wasnt strange at all.

He went inside, took off his jacket, hung it on the old nail by the door. Everything was, somehow, still right the bed, the table, the battered teddy still in its spot.

He parked himself on the little bench by the window. The sunshine flicked dust motes about the place. He ran his palm over the wooden frame, every groove familiar.

He thought of his children in their own homes, bickering over bills, busy building their own futures. He thought of his own plans, now doled out in seasons rather than years: just one more spring, a few more days hacking at the garden, another week or two perched on the porch in summer dusk.

He knew theyd end up selling it, probably quite soon. Five years, maybe. Sooner or later, theyd say theres no point keeping the place empty. Theyd be right, in their way.

But for now, the hut stood firm. The roof held. Spades lined up in the shed. The first green shoots poked through the old vegetable beds. He could still shuffle about, bend over, pick things up from the earth.

He wandered outside, circled the hut, paused by the fence. Nearby, someone knelt over their own bed, planting. Next door, washing flapped in the breeze. Life, rolling on.

The fear hed been carrying wasnt just about the plot or the garage. It was the fear of not being needed. Not by the children. Not even by himself. These places were proof he still mattered. They let him fix things, paint, dig, feel useful.

Now, that proof felt fragile. The law said something different, but sitting on the porch, George realised a simple thing the deeds didnt matter as much as he thought.

He poured hot tea from his thermos into his mug, sipped. The taste was a little bitter, but it didnt stab so much as it had that evening at the kitchen table. The decision was done. The price was clear. Hed given the children a big piece of what counted for him, but hed gained something too. The right to be here, not through paperwork, but through memory.

He gazed at the old lock, the bent key still in his hand. One day, itd be in Sophies or Toms pocket, or in a strangers palm. Theyd fit it into the door, not knowing all that had come before.

And strange as it was, that was okay. The world turns, things move on. All you can do is live in your places while they still feel yoursnot on paper, but in your bones.

He finished his tea, stood up. Went to fetch the spade, had to at least turn one bed. For himself. Not for the future owners, not for the children who may have already counted the pounds in their heads, but to know the earth was still there for him.

He dug in the spade, pressed down with his foot. The soil lifted, rich and dark. George took in the scent, and leaned in again.

It was slow going. His back and arms ached, but with every scoop the heaviness inside eased a bit, as though shifting old fears out along with the weeds.

As evening fell, he sat on the porch, wiped sweat from his brow, saw neat rows where hed turned the soil. A faint pink had bloomed at the edge of the sky. Somewhere, a bird called.

He looked round at the hut, at the nine-toed prints on the beds, at the spade propped up against the wall. He thought about tomorrow, a year from now, five years. There was no answer. But, sitting right there, he knew: hed found his place for now.

He stood, went inside, turned off the lights, locked the doors. On the porch, he paused a second, drinking in the silence. Then he twisted the key. Metal clicked.

George dropped the key in his pocket and walked back along the narrow path, taking care not to step on the ground hed just workedstill his, in all the ways that mattered.