I slipped into the delivery suite of St.Marys Hospital, London, as if the corridors were rivers of white light. The fetal heartbeat monitor unfurled its line like a silver serpent, steady and perfect. I stared at the ribbon of sound, thinking of the night the midwife, MrsBaker, had sent a very ill newborn home, and now I had to arrange cover with another obstetric nurse, MissHollis, to keep the admissions ward on its feet.

Is everything wrong? a trembling, heavilylined pregnant woman named Evelyn pressed her eyes into mine. Whats happening on the screen? You look so focused.

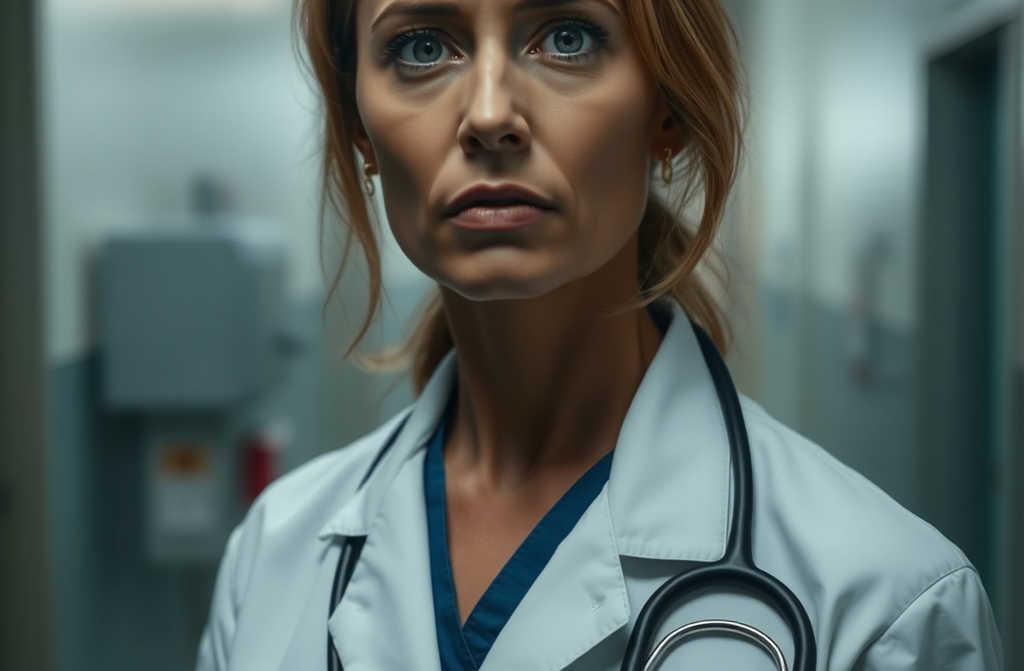

The hardest skill for a doctor is to keep the face. All our conscious lives are spent learninglearning to diagnose, to piece together crumbs of data into a whole, to observe, to wait patiently, to intervene only when needed, and to snap into the right decision in an instant. We are never taught the art of acting.

Imagine finishing a grueling operation at night, splashing the eyes with icy water, barely catching a breath before the blood that slipped through the gauze stains the heels of your shoes, then sliding down to the ward and greeting the next patient with a warm, sincere smile. That smile is the key that tells a frightened, bewildered souldelivered in the frantic ambulanceYou are safe, were glad youre here, help is coming, relief is near.

We were never taught that illness is terrifying. No matter how professional we become, no matter how we survive the hardest crises, we must cling to the mask of calm. Fear distorts realityboth yours and others. Beyond the hospital doors, parents fall ill, children lose their keys and perch on stairways waiting for someone, a mother in intensive care cannot stabilise a nonviable fetus, and a theatre nurse suffers a hypertensive surge. All this churns inside the mind, hovering above the visage we wear.

Holding your face is a monumental effort, especially when you realise you are fifteen minutes from disaster. You must conquer your own dread, issue clear orders, calmly explain to the patient why haste is essential, soothe her and her relatives, obtain consent for surgery, and race toward the trolleystripping off your coat as you runwhile keeping that composed mask.

Then, after the curtain falls, you step not back onto the stage but into the shadows behind it. The hardest moment comes when the catastrophe has already unfolded. Even then you must keep your face, forget the cold that settles in the chest, and keep talkingtalking to patients, to families, to strangers, to yourself, to God, to the frozen thoughts in your head, to superiors, again to families, again to the echo of your own voiceuntil the sharp pain in your ribs eases enough for a full breath, knowing another personal scar has been etched onto your heart.

An hour later, descending the stairs to see a new patient, you grip that mask tighter, rubbing the skin beneath your left clavicle as if to smooth out the cracks. Because doctors err. Every single one. Even those who claim a divine touch. They are human; only those who never work make no mistakes. Even the most precise machines falter, for they are built by hands that slip. The scariest revelation is recognising the exact moment you were wrong. Your mind loops back to the point where you could have acted differently, and the question hangswhat would have happened?without an answer, forever unresolved.

When you stared at an utterly normal ECG through tired, murky eyes, those eyes have been conditioned by years of fatigue. When you missed a perfectly ordinary lab result that no one else noticed, when you calculated dosages exactly as the protocol dictated, when you arrived too early or too late, when you read an Xray and saw nothingor something that wasnt thereyour vision was the same as yesterday, a month ago, a year ago. When a hand slipped with a scalpel and a vessel clamp snapped freewhy didnt that clamp fly the day before, the day before that, a year earlier?

Perhaps six nightshifts in two weeks are too many, especially when your mother lies at home, still recovering from a stroke. In medicine, time is a relative notion, while your loved ones have long occupied the dignified final seats. The most terrifying thing is not the mistake itself, but not understanding what you did wrong, for the error may repeat. How many more textbooks, trainings, sleepless nights must you endure to prevent the repeat?

Who can say? And how do you banish the thought that statistics haunt you? Grim medical statistics whisper, in a cold, disembodied voice, that out of a thousand deliveries, surgeries, or proceduresthree, five, ten complications will arise worldwide, every day, every month, every year. Someones life, someones health, someones tragedy is woven into those numbers. It is always someones.

What does a physician do when his name appears in those figures? He stands before grieving families and says, Here I am. Your killer. Can anyone truly imagine themselves in that role? When countless, profoundly unhappy people stare back at you, and you are, for them, the sole source of their boundless sorrow, you become the embodiment of death. Here I am, you proclaim, and the world crumbles.

Why, when a doctor errs once, are the countless times he was right erased from memory? Doctors err because they are human. Gods do not err. That is their realm, their creation, their statistics. The more I work, the more I realise that only the chosen can glimpse the purpose behind the numbers. We are not chosen. We are ordinaryordinary people, ordinary doctorsstanding in a surreal dream that never quite lets go of its own face.