In the sleepy village of Willowbrook, tucked away in the rolling fields of Yorkshire, no one was fond of old Lottie. Truth be told, she didn’t much care for them either—”didn’t much care” being a generous way to put it. The villagers unanimously agreed: Lottie despised people, and the feeling was mutual. Built like a plough horse, broad-shouldered and towering over most of the local lads, she made them crane their necks just to meet her gaze. Not that anyone wanted to. She never returned greetings, just muttered under her breath and marched on, eyes fixed straight ahead—or rather, down, given her height.

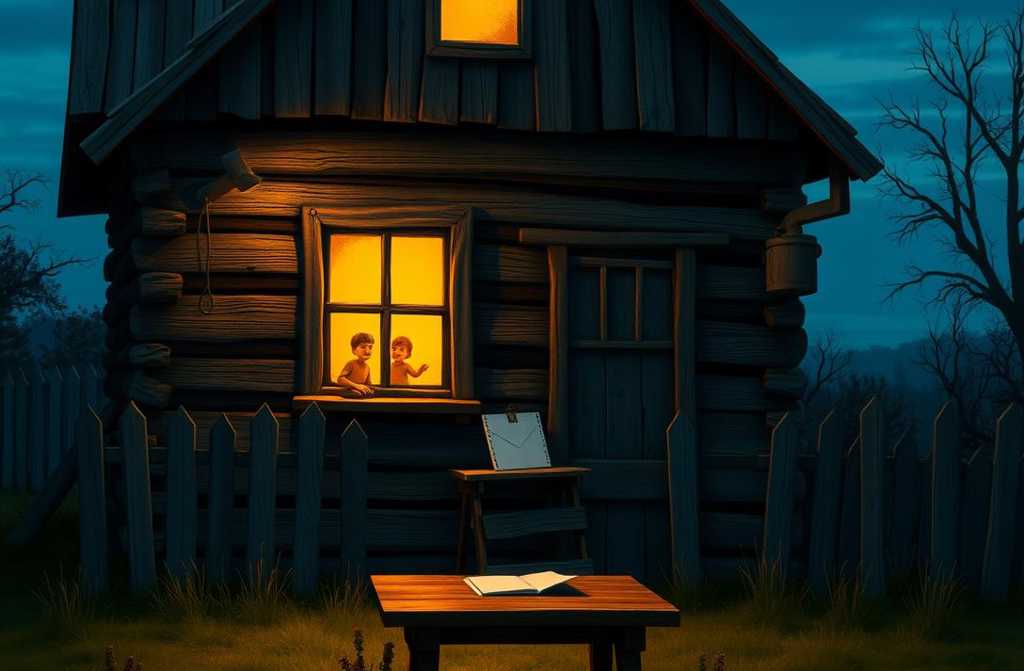

Lottie lived in the heart of the village, in an old timbered cottage her father had built, or so the elders remembered. A tall, solid fence encircled the place, so imposing that few dared peek over. She wasn’t one for patience, either. One summer evening, a couple of curious lads—having had one too many pints—clambered up for a look. Spotting them through the window, Lottie strode out with her father’s hunting rifle and, without a word, fired a warning shot over their heads. After that, even the bravest gave her yard a wide berth.

Her homestead was no small affair—chickens, geese, rabbits, and a pair of goats. The villagers whispered, “What does she need all that for? Her pension’d be enough, but she’s too tight-fisted.” She butchered the animals herself, carted them to market in the nearest town, and sold out by noon. The money vanished into her apron pocket before she retreated to her fortress. Her goat’s cheese, made to some old family recipe, fetched a pretty penny—regular buyers from the city, it was said. Her chickens were plump, rabbits well-fed, eggs colossal, and not a cheat in sight. Lottie never haggled, yet folk bought eagerly.

When talk turned to her, the old-timers recalled: Lottie had always been surly. Her mother died while she was still crawling. That left her and her father—a hulking, silent man. Years later, he brought home a stepmother from the next county, but she fled to the train station within a month, suitcase in hand. Some murmured it was Lottie who drove her off. So it was just father and daughter again—until he vanished on a trip to sell goods in the city. Murdered? Chasing that runaway wife? No one knew. Lottie was left alone. For good.

She never married. “Who’d put up with the likes of her?” the village gossiped. Years rolled by, generations came and went, yet Lottie seemed frozen in time. Even grey hairs dared not touch her—she always wore a scarf, revealing only a heavy jaw, a hooked nose, and dark brows carved like stone.

Then, one winter’s night, the Williams’ cottage caught fire. Without a word, Lottie appeared with a firehook and helped douse the flames before the brigade arrived. She worked so deftly, prying apart burning timbers, that the house was rebuilt from the same beams—barely singed. The Williamses thanked her, but Lottie just grumbled and stalked away.

When Lottie passed, the headmistress of St. Agnes’ Children’s Home, Beatrice Whitmore, arrived with three staff and a dozen wide-eyed youngsters. The villagers—more out of curiosity than grief—flooded into her yard. And there they found perfection: the chicken coop, rabbit hutches, goat shed—all immaculate, like something from a posh magazine. Inside the cottage? Spotless, but barren. A table, a chair, an iron bed with a saggy spring, a crooked cabinet holding one cracked plate, a spoon, a knife, and a chipped mug. By the window, a worn bench polished smooth by time. On the stove, neatly folded clothes. That was all.

On the table lay an envelope, addressed in firm handwriting: *To Beatrice Whitmore, from Charlotte Margaret Holloway*. The headmistress opened it and read a page torn from a notebook. Later, she told them: for twenty years, Lottie had sent hefty sums to the home—money that kept them afloat. The note read: *I leave the cottage, livestock, and all possessions to St. Agnes’ Children’s Home. The little ones bear no blame.*

The villagers stood silent, staring at the empty house. Someone remembered young Lottie sitting by the river, staring at the water as if waiting. Another whispered perhaps her father hadn’t vanished—perhaps he’d fled, leaving her behind. And so she’d carried that weight, locking her heart away—until, at last, she gave everything to children who’d done no wrong.