In the village of Willowbrook, tucked away among the rolling hills of Yorkshire, Old Lydia was disliked by all. She kept to herself—though “kept to herself” was putting it lightly. The villagers agreed on one thing: she despised them. Lydia’s health rivalled that of a workhorse—tall, broad-shouldered, towering over most of the local men, forcing them to tilt their heads just to meet her gaze. But no one sought that gaze; she never returned greetings, muttering under her breath as she trudged past, eyes fixed ahead. Or rather, not lowered—her height was formidable.

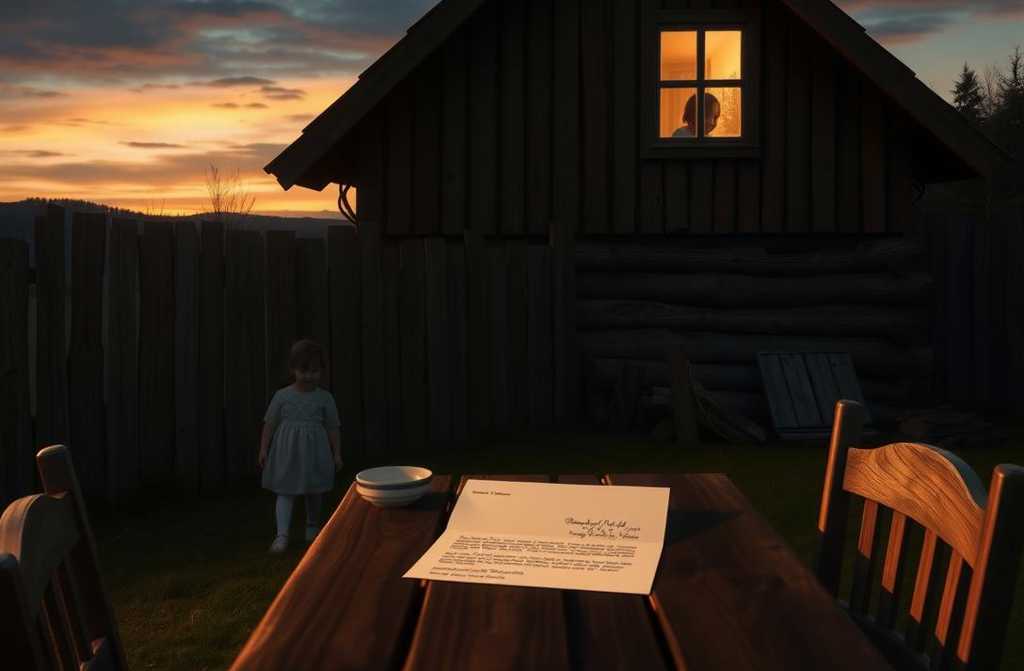

Lydia lived in the heart of the village, in an old cottage that, as the elders recalled, had been built by her father. A tall, solid fence surrounded it, so high few dared peek over. Lydia was quick to act. One summer evening, a group of curious, drunken lads climbed the fence to spy on the recluse. Spotting them through the window, she stepped onto the porch with her father’s old hunting rifle and fired a warning shot over their heads. From then on, her yard was avoided.

Her homestead was substantial—chickens, geese, rabbits, and two goats. The villagers whispered, “What does she need all that for? Her pension would suffice, yet she hoards like a miser.” She slaughtered the poultry and rabbits herself, carting them to the market in the nearest town, where she sold everything in a day. The money vanished into her apron before she retreated to her sturdy cottage. From the goats’ milk, she made cheese using an old recipe—expensive, but rumour had it she had loyal buyers in the city. Her produce was spotless—plump rabbits, large eggs—never a cheat. She never haggled, yet her goods sold fast.

When villagers spoke of her, the elders remembered: Lydia had always been grim. Her mother died when she was still crawling. She and her father—equally massive and unsociable—were left alone. Years later, he brought home a stepmother from the next county, but the woman fled with a suitcase to the train station within a month. Some murmured it was because of Lydia. So it was just father and daughter again. When Lydia grew up, her father left for the city to trade and never returned. Murdered? Gone after his runaway wife? No one knew. Lydia was left alone. For good.

She never married. “Who could put up with the likes of her?” the villagers clucked. Years passed, people died, children were born, yet Lydia seemed frozen in time. Even grey hairs spared her—always wrapped in a headscarf, only her heavy chin, hooked nose, and thick black eyebrows, sharp as chiselled stone, visible beneath it.

One winter night, the neighbours’ cottage, the Wilsons’, caught fire. Without a word, Lydia appeared with a fire hook and helped battle the flames until the fire brigade arrived. She worked so deftly, the house was later rebuilt mostly from the original timber—little had burned. The Wilsons thanked her, but she only grunted and walked away without a glance.

When Lydia died, the headmistress of the local orphanage, Miss Eleanor Whitmore, arrived with three carers and a dozen children. The villagers, more curious than mournful, crowded into her yard. Inside, they found perfect order—a henhouse, rabbit hutches, a goat shed—all spotless, like something from a country magazine. The cottage was sterile yet barren—a table, a chair, an iron bed with a sunken frame, a crooked cabinet holding one cracked plate, a spoon, a knife, and a handle-less mug. By the window, a worn bench, smoothed by time, and on the hearth, neatly folded clothes. That was all.

On the table lay an envelope, addressed in firm handwriting: “To Miss Eleanor Whitmore, from Lydia Grace Holloway.” The headmistress opened it and read a note torn from an exercise book. Later, she revealed Lydia had sent the orphanage money every month for twenty years—no small sum, a lifeline for the children. The note read: “I leave the cottage, livestock, and all possessions to the Whitmore Orphanage. The children bear no guilt.”

The villagers stood silent, staring at the empty cottage. Someone recalled how Lydia, as a girl, used to sit by the river, staring at the water as if waiting. Another whispered her father might not have vanished—perhaps he’d fled, leaving her behind. She carried that weight, locking her heart away. And in the end, she gave everything she had to children who were strangers, bearing no blame at all.

Some souls are like closed books—their darkest chapters hidden, their kindest deeds written in silence.