Dads Allotment

The news that our allotment had been sold came to me quite suddenly, almost by accident. Id called my mum at her new job in another town, chatting from the old red phone box down the road. You see scenes like it in films sometimes, when a person becomes the thirdaccidentalparticipant in someone elses conversation. The operator must’ve mixed up the connections because I found myself listening in on two people talking in different towns. In those couple of paid minutes, I heard the most important thing: the allotment wasnt ours anymore, itd been sold for a tidy sum, and nowwell, now there was enough money that even I, it seemed, might get a little help.

It was mum and her sister, my Aunt Irene. Such familiar voicesvoices that, at that moment, travelled the hundred-odd miles between us, split into vibrations and zapped down the wires. Physics never made much sense to me, but dad always insisted I stick at it.

***

Dad, why is September sunshine so different?

How do you mean, Olivia?

I dont know. Its softer, isnt it? Lights changed from August.

Ah, Liv, youve got to learn your physics! The suns at a different place in September. Here, catch Dad laughed and tossed me a massive, slightly squashed apple. Gleaming, red, heady with honey scent.

Bramley?

No, those arent ready yet. This ones a Worcester Pearmain.

I crunched into it, foamy sweetness flooding my mouth, summer rain and earths tang lingering on my tongue. I never knew much about apples or physicsand that was my biggest problem, really. Because for two years, Id fancied my physics teacher. It was as if the world had shrunk to beam of light, the rules of matter and space refusing to fit neatly on the lined pages of my homework. Dad saw it in my distant eyes and poor appetite. Of course, I confessed it last year, sobbing my heart out on his lap one night when mum was away at the spa, my older sister, twelve years my senior, studying in another city.

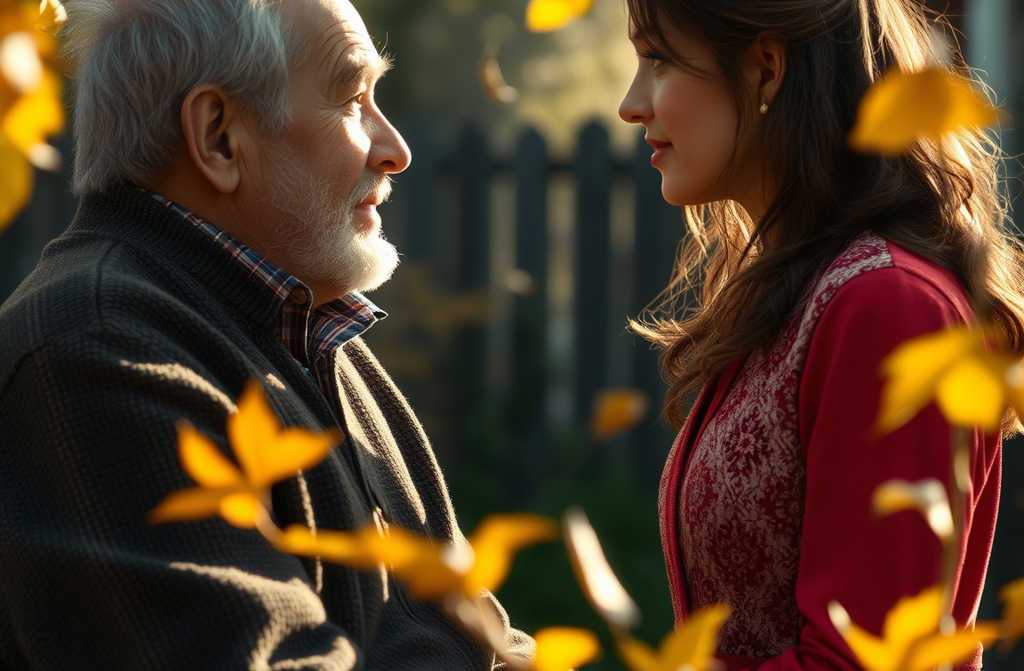

At the allotment, dad was always cheerful, whistling tunes. He never whistled at homethere, it was mum and my sister who made the noise. Mum, glamorous and tall, ran the library at the barracks. She was a head-turner, always with her copper curls, dyed with henna every other month. Shed emerge from the bath with a huge towel-turban, smelling of herbs and rain. Everyone noticed her beauty. Dad, meanwhile, was shorter, almost ten years her senior, quiet and, as mum once described to my sister (I overheard and took the words to heart), nothing to look atbut a man neednt be handsome.

Nothing to look at, perhaps, against mums fierce hair, boisterous temper, smashed crockery, unbridled spirit. Mum liked comfort and order. But she put up with the ‘squaddies,’ as dad called them, who sometimes slept on our living room floor. Hed been a major in the army before the big redundancies of the sixties, then worked as chief mechanic at the Reading telegraph exchange. Those squaddies, grateful all, helped dad build the allotment shedfree labour, one swapping for another, breaking the old soil. Our tiny shed, just a single room and a veranda, was perfect for reading on the roof in summer. Dad would send up bowls of gooseberries or strawberries for me. Bliss.

Mum hated the allotment, rarely visited, worried about her handsbeautiful, elegant with robust nails. I admired them; dad kissed them.

Hands like those are for handing out books, not shifting spuds! hed chuckle, winking at me.

***

Drops of September rain drummed merrily on the veranda roof. Olivia put away her book.

Liv, come down now. Mumll be back soon with Irene, and we need to sort lunch, dads voice rang clear, sounding oddly bright in the open air.

I hesitated. Head tipped back, feeling cool raindrops on my face. Hugged myself for warmth, scanning the neighbours plots and the sunbeams slicing through the clouds. The rules of physics forgotten amidst university shared housing and new routines.

They put me up in student halls straight away, but for that first week in September, I had to stay in a bedsit with the landlady, the other room filled by students. Lectures plunged me deep in literature, language, taught by the sort of lecturers that everyone fell for, their charm sweeping the entire group along. After classesI felt an aching loneliness, missing home, with no new friends yet.

I snacked at the cafeteria, wandered streets until dark. The citys strange beauty left me cold and isolated. Id walk down steep Ironmongers Hill by the main university building, along narrow terraced roads, dodging barking dogs, tripping and scraping my ankle in stiff new shoes.

The kitchen always smelled of dads apples, which, bless him, hed brought for the landlady. That pungent, slightly decayed fragrance brought tears to my eyes.

When I moved into halls, my neighbours turned out to be exchange students: Viola, Maggie, Marion, from East Germany. Listening to German every day gave me headaches, so Id step outside. The others chain-smoked on the front steps. The Germans would chase me up for cigarettes, always insisting on paying me backour girls found it odd! They loved my mums preserves, especially her pickled tomatoes, eating them with fried potato. When my stash ran out, theyd bring out their own sausagesfancy stuff, but never shared. In May, their placements ended; they left heaps of sturdy winter boots by the bins, ones they’d bought specially for English weather. Our lot quietly snapped them up

***

Liv, slice this cabbage will you? Ill dig up some carrots. Stocks ready now.

The kitchen windows steamed up. The massive cabbage sprawled, lime leaves fanned across the cutting board. Tearing off one leafdelicious. Food from our patch always tasted best. I chopped cheerily, sweetness filling the air. Crack the windowsmoke, autumn leaves, apples. I saw dad out back, shovel buried into the ground, moving heavily. His back pained him, I knew that. I tossed the knife down, dashed outside, hugged him from behind. He turned, hugged tight, kissed my hair.

That evening, only Irene came; mum had one of her bad headaches.

***

Time marched onuniversity, marriage to a fellow student, my reporting job at the local aircraft factory paper, dads first heart attack, the birth of my daughter (Lucy), even the divorce. Five years packed everything in. My husband left for someone else, so I lived with two-year-old Lucy in a rented flat. Dad visited every other weekend, arms loaded with groceries, always fussing over his granddaughter.

Liv, dont begrudge your mum missing visits, like I do. Long drives make her sick. Besides I think shes seeing someone.

Dad! At your age? Come off it!

Dad laughed, but it sounded terribly sad. He grew quieter, and I noticed hed gone almost entirely grey. Even stopped whistling.

Dad, shall I take a holiday next week? Lets have a last trip out to the allotmentwhile its still warm. The three of us, with Lucy?

***

Leaves blanketed the plot; the last warm spell of October and a touch of Indian summer. We lit the stove, brewed tea with blackcurrant leaves. I pan-fried potato cakes, dad raked leaves, Lucy tried to help before gleefully scattering them again. Butter crackled.

By dusk, we built a bonfire. Empty lanes, deserted plots. Dad showed Lucy how to spear thick bread cubes onto cherry twigs, roasting them over the fire. I stretched my frozen hands to the flames, mesmerised as ever.

Memories drifted backsinging songs round the campfire during my first student expedition out in Northumberland. Not love for anyone, just a vast, starry, dizzy love for the infinite night and silence, the off-key chords, the faces. Night changed all faces by firelight, each with its hidden stories and deep eyes. Thats where I met my future husband.

This week at work theyd called me in for the union meeting, considering my nomination to the Labour Party branch. The night before, Id crammed party rules and conference notes, only to be grilled about my divorce and character. I fumbled and nearly broke down, but then a colleague jumped up, stammering,

This is a gathering of ruffians, not comrades!

Years later, it would seem laughable.

Night fell, we doused the fire. A car pulled up at the gatedoor slammed. Mum! In a flashy coat, said a colleague from work had given her a lift. Lucy ran to her granny, dad frowned, awkwardly kissed mum.

Whos this friend then?

Oh, for goodness sake, Charles! He just drove me, you dont know him

Dinner was stiff, Lucy became cranky. Mum asked about work but was clearly somewhere else in her thoughts. Dad watched mum quietly, brow creased, shoulders slumped. The evening was ruined.

***

A year later, dad passed away. Heavy heart attack, gone in two days in early October, when the sun still shone. Right after the funeral, I took leave to spend some time at the allotment. Lucy stayed with my former mother-in-law.

Nothing went right. The apples, this year of all years, were bountiful. I gave buckets away, made vats of apple jam with mint and cinnamon like dad loved. Dads old army friend, Mr Johnson, came to help, driving down from Ipswich with some new shrubs.

Ill stay a few days, Livdig the garden, prune the trees, if that’s okay.

Oh, Mr Johnson, you dont have to Thank you!

Hearing dads old ‘Liv’ made tears stingright then the heaviness, the sense of being an orphan, truly hit. Before that, I half expected dad to stroll back in, as if it was all a bad dream. Those first mornings, waking up, it took forever to remember why everything hurt so muchthen the realisation washed over: dad was gone.

Worse came when I felt guilty for not keeping him here longer.

Dont sell the plot, will you? Ill keep visiting, help out. You know, Liv, we chose that Bramley together, you were just a slip of a thing. On the way to Ipswich, Charles talked more about you than your sister. You were a funny little girl. He used to say, The trees will outlast me. Hed examine every sapling for agesdrove me mad!

Mr Johnson stayed three days, dug the soil, pruned the apples, added fertiliser, and planted three yellow chrysanthemum bushes at the front with my blessing.

Ought to plant them earlier, but the autumns been warmtheyll take! For Charles Youll want to wrap the roses soon, tidy the leaves, but Ill do that next time.

We hugged at the gate, drizzle starting up. I watched him stride away; he turned, waved, told me to get inside. The rain picked up, beating a mournful rhythm. Wind slammed the gate, scattering chrysanthemum petals across the porch. Everything here was dads, and always would bethe rain, the trees, the autumn scents, even the soil. So hes close, always will be. Id learn, I promised myself. Wed visit with Lucy till the first frost, just two hours by coach. Maybe in spring, once the snows gone, I could get the plumbing sorted. I needed to start putting aside a bit more money. And next springMr Johnson and I would drive to Ipswich to pick out a whitecurrant bush. Dad wouldve loved that

***

Six months later, early April, when the last snow still clung to the ground, the allotment was sold. I learnt about it, once again, by accidentcalling home from the phone box on my way back from Ipswich. In the cramped booth, with my whitecurrant sapling wrapped tight in a damp babys vest in a carrier bag at my feet, I received the news.