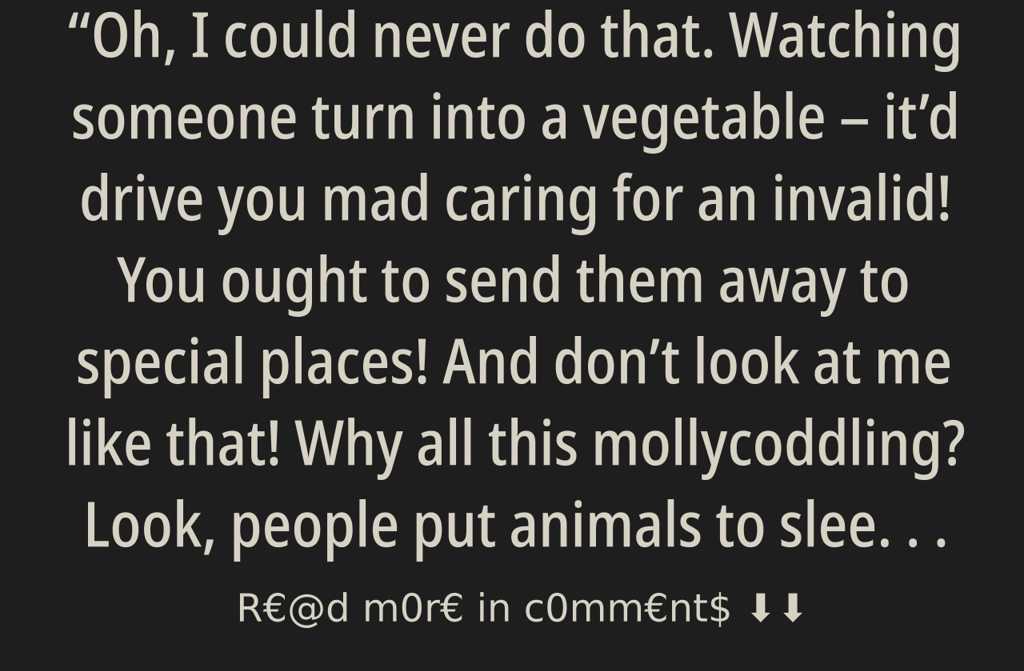

Oh, I could never do that. Watching someone turn into a vegetable itd drive you mad caring for an invalid! You ought to send them away to special places! And dont look at me like that! Why all this mollycoddling? Look, people put animals to sleep, dont they? No one bats an eye. Yet here we are, all terribly humane. Theres a country somewhere, you know, where they leave old folk up a hill far away, just leave them. And another thing Antonia was ready to keep ranting, but Alice cut her off sharply:

Antonia, have a bit of shame! Thats our mum youre talking about! What do you mean, a hill? Have you lost your mind?

Well, first of all, shes not our mum, shes your mum. Shes my husbands mother. Theres a difference, admit it. And even if she were mine, Id do the same if she got like this. Come off it, Alice, looking after babies is one thing sweet as anything! But full-grown, utterly helpless? Sorry, reeking to high heaven, with no hope? Speaking of which, whats happening with her flat now youve taken her in? Its just sitting empty. We ought to sell before house prices go down. Our Sam needs money for school, Peter wants to get married. We need it more, really. Your daughter was born late when will she even be grown? Be reasonable, hand over the place to your brother and Antonia ran out of steam as Alice glared.

Alice, darling! Alice, where are you, sweetheart? drifted through from the bedroom.

Youd better go in, Toni. Mums woken up, Alice said quietly, nudging her sister-in-law toward the hall.

Her head felt thick as coal smoke, her mother ached all over and hadnt slept in days. Still, a thought tickled at her: What if Mum had heard the entire conversation? How awful would that be?

Alice entered the room. She had to fling open the window; the air clung, heavy and suffocating. Yet Mum was always cold, shivering, so she wrapped her tighter in her shawl. Mums head swivelled when she heard the footsteps. She straightened in bed, smoothed her wispy hair a bit. Alice looked at the hands workers hands, big and paddle-shaped but with long fingers, their veins tracing blue patterns. Mum fiddled with the blanket, her eyes vacant and fixed in one direction. She couldnt see. They said there was some chance a bit of vision might return in one eye, but Alice no longer believed. She changed the tangled sheets and helped her eat as she always did. Mum curled up and drifted off again. Alice dashed out to the doctor. She needed advice her mind felt soggy as porridge and she wanted to bolt from her problems.

She stood for an age, grumbling about the lack of improvement, about how hard it all was. The doctor, smartly dressed and bearded, hurriedly filled in forms, the queue trailing down the corridor. He looked up, his eyes weary.

Must be hard work, all this, for you, she heard herself mumbling.

Heaps of work. Never enough doctors. If I could put the same medicine in a bottle for everyone, hand it around, thered be fewer patients, smaller queues, he almost smirked.

What medicine? Can we get it? Alice perked up hopefully.

Youth, he said, quietly. Why the sudden long face? You say youre tired I understand. But did your mother complain? Did you fall ill as a child? Did she ever ignore you at night? Removing his glasses, he awaited her answer.

Alices mind offered up a flurry of scenes without prompting. She was eight, feverish with the flu. Mum scooped her up and carried her, though it was a strain. Mum made her tea with lemon, found cranberries from God knows where. Once, late at night, she fancied blackcurrant juice. Mum vanished into the night, reappearing with berries. Come morning, the temperature had dropped, Alice finally slept, but Mum went to work. She always worked at two, three jobs so Alice would have the best of everything.

There was the time, in December, outside a shop window. Inside was the most beautiful, silvery shimmering dress Mum ever saw. Yet after a wistful gaze, she turned away, stroked Alices cheek, and led her to get a new coat, new boots buying nothing for herself. Then there was the fairy-cake: pink and white, tiny, a rare treat in times of rationing. Alice ate nearly all of it; Mum had only the faintest scraping of icing. Alice, guilt-stricken, glanced up. Mum hugged her close, saying, Never mind, darling, well share more cakes one day.

Children grow up and forget how much of themselves their parents gave. Werent you ever little and helpless? Now your mums become that. So, what is it you want to do, truly? I know youre worn out. Just for a moment, dear lady, imagine life if your mothers gone. Suddenly, youd be freenights to yourself, no need to get up and fuss. Would that be happiness for you? His voice was steel-wrapped velvet.

I… Yes Well. Ill follow your advice. Sorry for coming like this, Ill be back later! and Alice bolted from the surgery.

Hot cheeked, she walked blindly, scolding herself. How could she wish her mother away? Shed never manage without her. No matter her age, she still needed her mum. How many times had she wept into her lap, or found comfort in knowing, Once this passes, I can go home to Mum. Shell know what to do. Her phone buzzed: Jack, her brother.

What do you want, Jack? Antonias been here already, after the flat? Take it, take the blooming lot! Mum loves you so much, always asks after you. And you? When you broke your leg and couldnt move for months, who cared for you? Who kept both of us together? It was just her, and Alice hung up in frustration.

Oblivious to puddles, she wandered aimlessly through the rain, tears streaking her cheeks. At last, she reached a shop. In the window was a dress: almost the same one. Alice rushed to the counter.

Its only left in that size, too small for you, Im afraid, said the shopgirl softly.

I know! Wrap it up, please. Not for me. For my mum. Shes a slip of a thing. I know it wont fit me, Alice sniffed.

The girl blinked. The dress shimmered on the counter. And what of it? Alice bought a cake on the way home, just like those in her childhood: a pink-and-white swirl. Mum wouldnt see it, of course, yet Alice would describe it to her, every detail.

Taking the stairs two at a time, she burst into the flat. Down the hall, her daughter Jennys voice floated from the door. Alice entered. Jenny sat by her granny, stroking her hair, singing a quiet tune. Mum smiled beatifically.

Oh, Alice. Love, you must rest awhile youre wearing yourself out, my lovely girl. Im so sorry to be so much trouble, Mum said gently, blindly stretching out a hand.

Alices throat closed up; she could barely breathe. We are all tested, she thought. But not everyone rises to the moment. I nearly failed.

Mum she breathed, burying her face in those familiar hands.

She knew then: as long as a parent lives, you are a child. When they are gone, no matter your age ten, twenty, forty, sixty youre an orphan. We all need a mother.

Mum, Ive bought you that dress. Like the one in the window, the silvery one. And a cake, like we had before. Well get you dressed up and have tea youll be the belle of the ball! Alice brushed out her mothers hair.

Mum shyly fingered the new dress, a gentle smile flickering on her lips. They dressed her up. Alice styled her hair, Jenny fetched some perfume and lip balm, put the kettle on. They drank tea and reminisced. Alice could only marvel how beautiful her mother looked serene and warm. Faces like that are nearly gone from the world, she thought. That generation carried a perennial goodness. In all her mothers pain and suffering: not one complaint, not one groan.

A sharp knock. At the door it was Jack. He stood there, arms full of flowers and a pineapple.

Pineapple, Jack? Why the pineapple? Alice exclaimed.

Well, Mum said she fancied one years ago, but we couldnt afford it then. So now Alice, Ill bring pineapples every day if you want. And dont listen to Antonia. Dont let her twist things. Let Mum live here for as long as she wants. Im not after any square feet. She can move over to mine when shes better, well crowd together for pies as always! Jack grinned.

He entered, marvelling at Mums sparkling dress. She giggled like a girl, embarrassment and delight written across her face. Alice saw it for a moment, illness vanished.

Days slipped into one another, yet things changed. Alice let herself imagine, heard herself shout in her head, What if Mum were gone? Now, she treasured every moment, fiercely fighting for every extra day together.

I used to fear coming home to find Mumgone. As she grew more childlike, I bathed her, braided her hair, whispering over and over, Just live, Mum. However you are, just stay with us! shed tell the family.

Alice chased out grief and gloom from the flat, filling it with light and laughter. She told funny stories; she promised Mum would be up and about soon. She turned each day into a small celebration: some days filling the flat with balloons and bunting, others singing karaoke, because Mum adored a song. And, as it turned out, still had a beautiful, ringing voice.

Alice, is that something yellow on you? Mum asked one afternoon.

Alice dropped her cloth. She was in a yellow frock with little flowers.

You You can see a bit? Oh, Mum! Oh, what a blessing! she cried, hugging her tight.

By degrees, Mum started shuffling along the wall, then taking steps. There was no greater joy for Alice. Of course, she didnt let Mum go back to her own empty flat. Better together, always close, you never know.

Three girls living here now: me, you, Jenny. So much still to do! You promised youd teach me to bake bread still got the tins. But I always burn my pies. I can cook anything else, but cakes and I never get on. Jack promised to come by too, Alice would say, showering Mum with kisses.

Her brother was a mountain of a man, tall and strong, their affectionate big bear. Hed scoop up Mum and carry her out to the garden bench, sitting beside her, Alice watching fondly as their mother, delicate in her new coat and hat, sat as neat as a doll.

And, for once, peace came. Step by step, Alice saw things were possible again, as long as Mum lived. Just to hear her voice each day. Mothers are sun and water to us; without them, we wither.

What more to wish for? May mothers hearts always beat strong. May they get more care and surprises from their children a bunch of wildflowers in the rain, a dress with no occasion to wear, a little vial of perfume. And above all, may they always hear, while they are still here:

I love you, Mum. Please, always stay. You are the best thing in my life.Mum squeezed Alices hand, a surprising strength in her thin fingers. Oh, my darling girl, I wouldnt leave you. Not till youre grown up, she teased, her lips quirking with mischief. They all laughedAlice, Jenny, Jack, even Mum, the sound filling up every empty place in the flat. Outside, rain silvered the windows, but inside was warmth and light, and a sweetness that tasted like hope.

After tea, Alice tucked a woolly blanket around Mums knees, now rosy from the warmth. Jenny sang her a silly song about pineapples and princesses while Jack raided the kitchen, emerging with jam and bread for everyone.

For a moment, the world paused. Grudges faded, old bitterness softened, and the flatonce cramped with worry and unspoken wordsfelt boundless, buoyed by laughter and memories and the sense that, as long as they were together, there would always be enough. Enough time. Enough love.

Mum dozed as the lamp cast halos across her silvery dress, crumbs of cake on her lap and a faint trace of perfume in the air. Alice watched the slow, steady rise of her chest and finally, quietly, let herself breathe.

Tomorrow might bring strugglemore hospitals, more pills, more quarrels over flats and fading strength. But tonight belonged to them: the mothers and daughters, the brother with his pineapple, the child with her song, all holding tight.

The clock on the wall chimed gently. In its echo, Alice knew: sometimes, the greatest inheritance is not a flat, or a dress, or even a cake shared for tea. It is simply the promise said out loud, again and again, so no one can ever forget:

I am here. I always love you. Youre never alone.

In that small, golden moment, they truly werent.