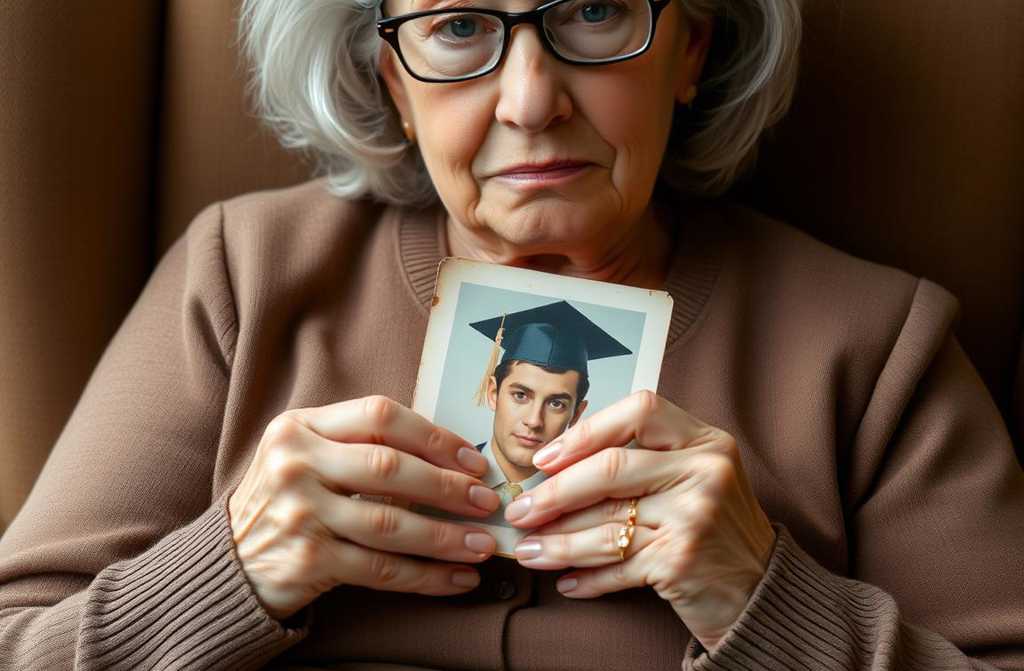

Betty Smith was tidying her deceased husband’s things when a graduation photo slipped from a dusty box. Forty years ago, she stood beside Michael, his arm draped awkwardly over her shoulders as if she might startle. The picture captured smiles, but Betty remembered the tremble in her hands when Mike nervously asked for a snapshot together.

“Betty, mind if I join you? For old times’ sake?” he’d mumbled, blushing furiously while inspecting his shoes. She’d just nodded silently, heart pounding like a drum solo everyone in the school hall surely heard. All that final year, he walked her home, carried her satchel, helped with maths. She pretended not to notice, feigning indifference.

Now, sorting Victor’s belongings, Betty saw all the might-have-beens. Victor was a good man, a devoted father to their two children, her partner for thirty-five solid years. Yet her heart always held a space for that bashful lad from graduation day.

“Mum, what are you digging at in there?” Her daughter, Beatrice, peered into the bedroom. “Need a hand?”

“Just sorting photos. Look – I was ever so young,” Betty passed the picture.

Beatrice studied it. “Who’s that with you? Doesn’t look like Dad.”

“A classmate,” Betty replied curtly.

“He’s rather handsome,” Beatrice grinned. “Looks smitten! Proper sweet on you?”

Betty turned to the window. Outside, October rain drizzled, yellow maple leaves caught in the drops.

“No romance. Just friends,” she said softly, adding quickly, “He went off to polytechnic college. I got into university. Different paths.”

Beatrice shrugged, put the photo down, and left. Betty was alone with her memories.

After graduation, they’d only met a handful of times. Michael visited her house. They sat at the kitchen table drinking tea. Betty’s mum, Eleanor, clearly approved.

“Lovely young man,” she’d say. “Hardworking. Sensible. Looks at you like you hung the moon.”

“Mum, don’t be daft,” Betty brushed her off. “Just friends.”

“Just friends,” Eleanor sighed. “At your age, I was picking my wedding bouquet.”

His last visit was in August, before university started. Betty was prepping for medical school. Chemistry and biology textbooks towered on her desk; her floor was buried in notes.

“Am I disturbing?” Michael asked at the door.

“Come in,” Betty nodded, nose still in her book. He sat opposite, quiet for ages. Then he spoke.

“Bet? What if we got hitched?”

Her heart lurched. She looked up, meeting his earnest gaze. He sat bolt upright, hands clenched on his knees, each word sounding like an effort.

“I mean it,” he pressed on. “I… I really love you. Have done since Year 5. Never wanted anyone else. You go to uni. I’ll work. Save up. Wait ’til you finish, then… family.” Betty stared. A ‘yes!’ fizzed inside her, wanting to fling her arms around him. But something stopped her. Fear of seeming flighty? Wanting a degree first? Or fear of feelings that serious?

“Mike, I—” she started, but he interrupted.

“Don’t answer now. Think on it. I’ll wait.”

A week later, Betty left for university in London. She never answered. When she returned as a student, Michael was seeing her classmate, Susan Wilkins.

Betty sighed, setting the photo aside. Decades later, it felt like yesterday: Susan proudly flashing her engagement ring; Michael’s awkward nod meeting Betty on the street; her chirpy congratulations.

At uni, she met Victor. He was a year older, confident, handsome. Persistent in his courting – bouquets, trips to the West End. They married in her third year. A big white wedding; everyone was green with envy.

“Mum, did you love Dad?” Beatrice asked once, grown up herself.

“Course I loved him,” Betty replied.

And it was true. She had. Just differently, less intensely than perhaps she might have loved Michael – but warmly, familiarly. Victor was a good husband and father. Steady job as a solicitor, home on time, never strayed. Betty worked as a GP, raised the kids, ran a tidy house – your standard, decent family life.

She’d occasionally spot Michael around town. Ageing, greying, wrinkled. But his eyes stayed the same – kind, a bit sad. They’d exchange weather pleasantries, updates on children. Betty knew he and Susan had three kids, that he was a foreman at a Leeds factory, living in a small terraced house on the city fringe.

The last time was at the hospital. Victor was in cardiology after a heart attack; Michael was in the next ward. Heart trouble too. They collided in the corridor.

“Bet? That you?” He looked stunned. “What brings you here?”

“My Victor’s a patient,” she explained. “And you?”

“Oh, bit of a turn,” Michael waved dismissively. “Docs say too much graft, nerves…”

An awkward silence hung. Then he asked out of the blue:

“Remember… when I asked you? At your mum’s kitchen table?” Betty nodded. How could she forget?

“Stupid git, I was,” Michael sighed. “Shouldn’t have asked for marriage then. Should’ve just said I loved you. Might have got an answer…”

“Mike, don’t,” she whispered. “What’s the point now?”

“Dunno,” he continued, ignoring her. “I sometimes wonder. How we might’ve been? You a doctor, me a shop floor bloke. We’d have had bonny kids, eh?”

*”You have lovely kids,”* Betty tried changing tack. “Susan showed me snaps.”

“Oh aye, grand kids,” he agreed. “Just… not *it*, know? Like living life slightly off-kilter. Respect Susan? Course. Smashing woman, keeps corners cleaner than God’s own fridge. But you… only ever loved you. Still do.”

Betty felt her knees weaken. Leaning on the wall, looking at this weary, ageing man, a stark truth hit her: So had she. All these years, she’d loved *him*, not Victor. Just hadn’t dared admit it.

“Mike, I—”

“Mr Turner! Doctor wants you!” A nurse called.

He nodded, turned back. “Go to your Victor. Get well soon.” She wanted to speak, but he was already shuffling down the corridor, stooped, hand grazing the wall.

Victor recovered, went home. A month later, Betty heard Michael died. A second attack. Gone before the ambulance arrived.

At the funeral, she stood apart, watching Susan sob, children weep. Not a tear fell from Betty. Inside, she’d turned to stone.

At home, Victor asked, “You alright? Got a bug?”

“No, just knackered,” she lied. That night, muffled sobs into her pillow wept for words never spoken to Michael. That she’d loved him forever. That she’d slowed passing the factory gate, hoping for a glimpse. That she’d kept every photo of them.

Now, packing Victor’s things – gone six months herself – Betty thought the same thoughts. Utterly alone with her ghosts.

“Mum, are you coming for supper?” Beatrice called again.

“Coming,” Betty answered.

She picked up the graduation photo, studied it, then held it tight against her chest.

“Forgive me, Mike,” she breathed. “I did love you. Always. Just… didn’t manage to

The photograph stayed on the dresser, frozen in hopeful youth as Eleanor shuffled toward the kitchen and whatever culinary adventure her daughter had managed to create this time—proof that roast chicken could indeed emerge looking vaguely volcanic.