**Diary Entry – March 16th**

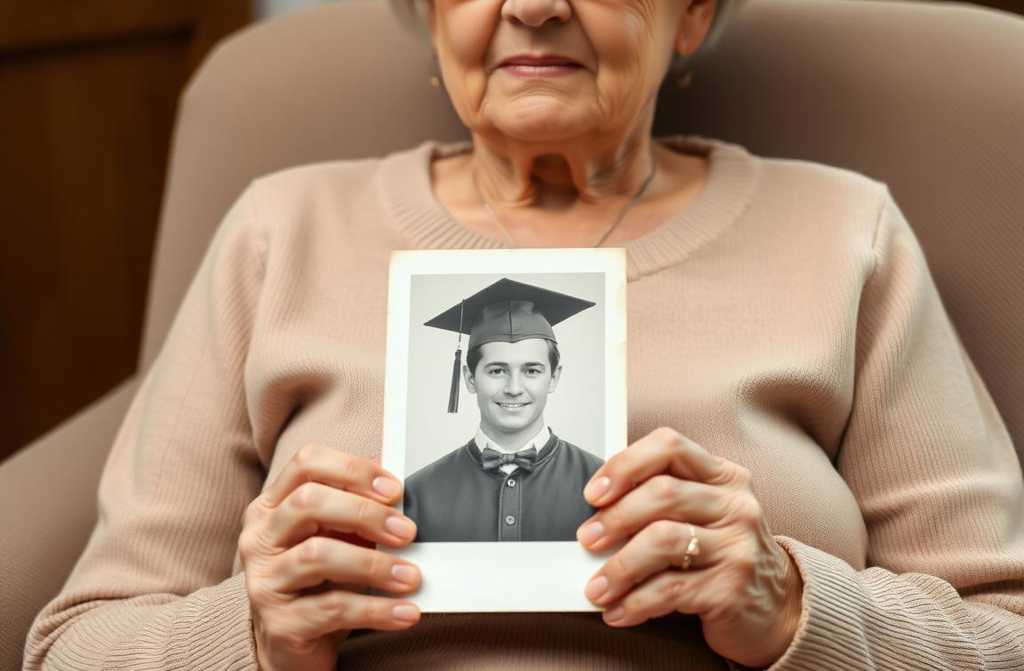

Found myself sorting through Aunt Margaret’s things after she passed. Poor woman. Came across a box of old photos while clearing her bedroom. One caught my eye – her school-leavers’ ball, forty years gone. There she was, young Margaret Cavendish, standing beside Michael Aldridge. He had his arm around her shoulders, ever so careful, like she might startle. Both smiling, but Mum later told me Aunt Margot confessed her hands were trembling that night when Michael asked for the picture.

“Margot, could I… might I have one with you?” he’d supposedly stammered, blushing fiercely, avoiding her gaze. “Just… for old times sake?”

She’d nodded silently, heart pounding fit to burst. That whole last year at St. Anselm’s, he’d walked her home in Tavistock, carried her satchel, helped her with maths. And all the while, she pretended not to notice, played it cool with him.

Sifting through her things now, months after Uncle Thomas died, I understand she saw the missed chances. Thomas was a good man. A solid thirty-five years together; two fine children, a respected GP himself. But, Mum said, her heart always held space for that shy lad from the ballroom.

“Dad, what’s keeping you in there?” Emily poked her head round the door. “Need a hand?”

“Just these photographs, love,” I replied. “Look how young your Gran was.” I handed her the snapshot.

Emily peered at it. “Who’s that with her? Doesn’t look like Grandpa.”

“Schoolmate,” I said shortly.

“He’s handsome. Looks at her so… adoringly,” Emily smiled. “Was there a romance?”

I turned to the window. Rain, typical March drizzle, streaked down the pane, blurring the yellowing oaks across the street.

“No romance. Just friends,” I murmured, echoing what Aunt Margot would have said.

Then I added, perhaps defensively, as she often had: “He went to the technical college in Plymouth. She went to Manchester University. Different paths.”

Emily shrugged, put the photo down, and left. I was alone with Aunt Margot’s story, the one she’d finally shared with Mum before the end.

They met only a few times after the ball. Michael would come around to Tavistock, sit in the cramped kitchen drinking tea. Her mother, Eleanor, approved. “Good lad, Margot,” she’d say. “Hard-working, steady. Looks at you like you hung the moon.”

“Mum, don’t be daft,” Aunt Margot would protest. “Just friends.”

“Friends,” Eleanor would sigh. “I was planning my wedding at your age.”

The last visit was late August, before term started. Aunt Margot was deep in revision for medical school, chemistry and biology texts piled high on her desk.

“Am I bothering you?” Michael asked from the doorway.

“Come in,” she’d replied, barely looking up from her book.

He sat opposite her, quiet for a long while, then spoke: “Margot… what if… what if we got married?”

Her heart stopped, Mum said. She’d looked up. Michael sat very straight, hands clenched on his knees, every word clearly costing him great effort.

“I mean it,” he stumbled on. “I’ve… I’ve been in love with you since Year 8. There’s never been anyone else. You go to university. I’ll work – I’ll train as a foreman, save for a place. We’ll wait ’til you’re done, then… proper family.”

She’d stared at him, Mum recounted, unable to speak. Her chest felt tight; she wanted to shout “Yes!”, throw her arms around his neck. But something held her back. Fear of seeming rash? Wanting her degree first? Or simply daunted by the sheer weight of his feeling?

“Michael, I…” she began, but he cut her off.

“Don’t answer now. Think about it. I’ll wait.”

A week later, Aunt Margot left for Manchester. She never gave him an answer. When she returned for holidays a student, he was walking out with Susan Archer, a classmate.

Aunt Margot sighed, Mum told me, putting the photo aside that day. Decades gone, yet fresh as yesterday. How Susan proudly flashed the engagement ring, how Michael nodded awkwardly encountering Margot on the street, and how Aunt Margot offered congratulations and “all the best.”

At uni, she met Thomas Harris. He was a year ahead, handsome, confident. Pursued her earnestly – flowers, theatre dates. They married during her third year. A big, smart registry office do; everyone thought it splendid.

“Mum, did you love Dad?” Emily once asked Aunt Margot, when she was grown.

“Of course I did,” she’d answered firmly. And it was true, Mum confirmed. She loved Thomas deeply, sincerely – differently, less wildly than she might have loved Michael, perhaps, but earnestly, as a partner and mother. Thomas was a good husband and father, a reliable solicitor, steady, faithful. Aunt Margot worked as a GP, raised the children, kept house. An ordinary, decent life.

She still saw Michael sometimes. Aged, wrinkles, grey hair, but his eyes unchanged – kind, a bit sorrowful. Brief hellos about the weather, the children. She knew he and Susan had three kids in the end, that he’d become a workshop foreman at the Manchester engineering plant, living in a small council house.

The last meeting was in hospital. Thomas was in coronary care after his heart attack. In the next ward, by chance, was Michael. Heart trouble too. They bumped into each other outside the lifts in that sterile corridor.

“Margot?” He’d blinked, disbelieving. “What are you doing here?”

“My husband’s unwell,” she explained. “You?”

“Bit of bother,” he’d brushed it off, Mum said he’d told her. “Docs say too much work, too much worry…”

An awkward silence hung. Then, unexpectedly: “Remember that day? In your kitchen? When I asked you to marry me?”

She’d nodded. Of course.

“Daft I was,” Michael sighed, Mum recalled his words. “Shouldn’t have proposed then. Should just have said ‘I love you’. Maybe you’d have answered differently…”

“Michael, don’t…” she whispered.

“But I still wonder, sometimes,” he pushed on, ignoring her. “How’d it have been for us? Good, I reckon. You the doctor, me the foreman… We’d have raised bonny kids.”

“You’ve lovely children,” Aunt Margot tried steering away. “Susan showed me photos.”

“Aye, lovely kids,” he conceded. “But… it’s never been right. Understand? Lifelong, not right. I respect Sue. She’s a wonderful woman, keeps a spotless home. But you were the only one I ever loved. Still am.”

Aunt Margot told Mum her legs nearly gave way. She leaned against the wall, looked at this tired, older man, and the truth hit her like a train

The photograph rests on the dresser now, Michael’s eyes forever holding that quiet devotion which lingered long after we both left this world behind.