One of those days when it doesn’t ache—just gnaws.

At the bus stop near the old market hall in Grimsby, a woman stood smoking, shielding the flame from the blustery wind with her palm while clutching a faded canvas bag with the other. The bag sagged heavily—not from the weight of objects, but from burdens too familiar to name. She stood at the very edge of the pavement, guarding that square of ground like the last stable fragment in a shifting, blurred world.

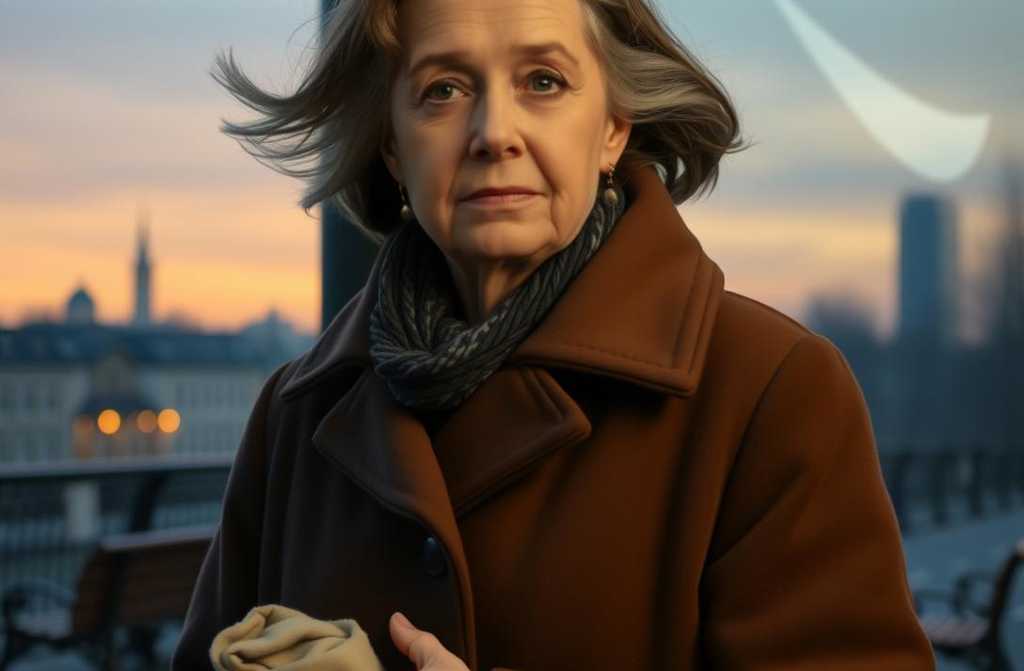

Her name was Eleanor. Forty-eight, but she looked younger. A lean face with sharp cheekbones, hair twisted carelessly into a knot, eyes pale but shadowed beneath—not from sleeplessness, but from the absence of things: attention, warmth, the occasional flicker of magic.

She wasn’t broken, just weary. Weary of days that blurred together, the screech of the alarm, the hollow phrases—“fine,” “same as always”—that masked the truth. Weary of evenings that ended soundlessly, without questions, without another’s presence beside her. Weary of reassembling herself each morning just to make it through.

She woke at seven. The floorboards creaked—her son, Oliver, leaving for college. He tossed a casual “morning” over his shoulder before the door clicked shut, never glancing toward the kitchen. She lay there a moment longer, staring at the ceiling’s hairline cracks, then rose.

In the mirror—just a face. No anger, no joy, not even irritation. Just a face. She drank her coffee standing, leaning against the counter, pulled on her coat, grabbed the bag, and left. The day didn’t begin—it simply resumed.

Today meant a trip to Lincoln—collecting paperwork, a rushed visit to the neurologist, and, if luck held, finding Oliver a new jacket. The pavement was slick. People hurried past; she walked with the bag pressed to her side, as if it were her only shield. Along the way, she bought two pasties. Ate one, wrapped the other in a napkin—for the man who usually sat by the underpass. But he wasn’t there. She left the pasty on the bench. Just in case.

The doctor’s waiting room was full—four elderly women chattered about blood pressure, their allotments, and the cramped consulting room where “that poor doctor must be suffocating.” Eleanor sat against the wall, scrolling through news. Explosions, deaths, other people’s tragedies, other people’s glossy smiles. Lives too distant to touch. She locked her phone. Not because it was too much—just because it no longer mattered.

The neurologist spoke of “autonomic dysfunction” and “the need for rest.” She nodded, pretending to listen. All she could think was: where is there a place to lie down and not think? To stop being strong, stop smiling, stop holding on. To vanish, just for a day.

Outside, the air had turned sharp. Wind slipped under her collar. She bought a paper cup of tea, sipping it slowly, as if it were the last warmth left. Sat on a bench in the square, bag pressed to her hip, breath catching in her scarf.

A man settled beside her. Mid-fifties, perhaps. Wrinkles around his eyes, shoulders tired. Without looking at her, he said quietly:

“Bit cold. Still don’t fancy going home.”

She wasn’t surprised. It was as if he’d spoken her thoughts aloud. They talked. About work. About food. About how odd life had turned. He was a night security guard at a corner shop; his wife had gone to stay with their daughter and likely wouldn’t return. The letters came less often now. He didn’t open them.

She worked at the post office. Lived with her mother, who forgot names, dates, even her own reflection some nights—wandering the house, searching for her long-dead husband. They spoke calmly, almost casually, as if discussing the weather instead of the weight they carried.

Silence. Sips of tea. The wind tugged at his coat. Then he stood, hesitating before saying:

“Mind if I remember you?”

“No. Just don’t get me wrong.”

He smiled, then—the first time. “Won’t. Just nice to know someone else is real. Not on a screen. Not in telly. Actually here.”

He walked away without looking back. She watched until the wind swallowed him.

That evening, Oliver returned. She reheated dinner, asked about his day. He shrugged, scrolling on his phone. Then, abruptly, he glanced up:

“How was yours?”

The fork stilled in her hand. Those four words—something flickered inside. She answered slowly: “Just another day.”

He nodded. Didn’t look away immediately. It was a small thing. But in her world, where days bled into each other like carbon copies—even that meant something.

Later, lying in the dark, she wondered: maybe someone, somewhere, was remembering that bench, the tea, the quiet that held space for a stranger’s kindness.

And that thought was enough. Not a miracle. Just an anchor. Enough to rise again tomorrow. And step out—into one of the next days.